Ibrahim Chabbouh

During a long association with Islamic Arabic manuscripts, both text and materials, two things have attracted my attention:

- The breadth of Islamic culture as expressed in the Arabic script, its variety of materials and its wide distribution in the form of autographs and manuscript copies.

- The techniques which lie behind a handwritten book and which were used to make every constituent part of it.

Understanding the second point is more complex, due to the rarity of documents which might clarify it, and the dependence of research, in most cases, on technical analysis and the existence of suitable material for comparative study.

It took me some time to collect texts about the production of book material since the early ages of Islam. Through these I became, to varying degrees, familiar with:

- The production of parchment and the methods of polishing, colouring, and preparing it for writing.

- The production of paper, a special process encompassing various technological complexities, and its raw materials and methods of processing and manufacturing them.

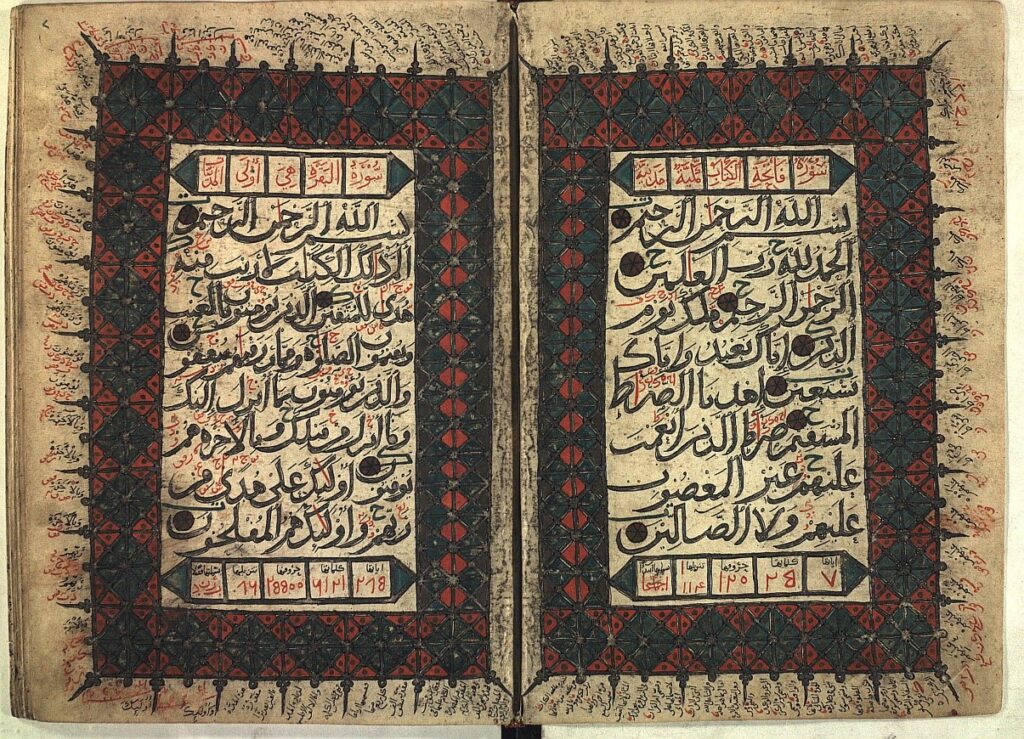

- Papyrus, the earliest sheet writing material and the most sparsely documented, except for some 'nature' references and data in a few botanical and pharmacological books.From the early Islamic ages we have plenty of documents, correspondence, fragments of once-complete copies of the Qur͗ān, and a large part of the Jāmi͑ of ͑Abd Allāh b. Wahb al-Miṣrī, dating from the 2nd century AH.

- The production of ink, in many colours, and its mineral and vegetable component parts. The documents on ink outweigh, in number and clarity, the documents on other aspects of book production. Among them I have found some important and early texts about mixing proportions, which ink is suitable for parchment, and which is suitable for paper, and other technical secrets and explanations related to the production and fixing of colours.

- The binding industry, as first set out in Moroccan and Andalusian texts. There are also a great many historic books, kept in libraries, museums and private collections, that provide a visual testimony to various artistic schools of binding which flourished throughout the history of Islam.

The numerous documents which I gathered have answered a question which had preoccupied me for some time: was all this manuscript heritage (with its materials, instruments and connected processes) established without the names and terminology needed to crystallise it in the mind?

How were the concepts behind the terms determined across the Arab world, and unified by the common denominators of one civilisation? Were verbs adapted to suit every technical process, with the meaning inflected to indicate only this one process, whilst the original word retained other meanings, as was always the case with the evolution of any term?

This is not all. I was surprised to find out from my readings that the literature and language of this craft were not restricted to its practitioners, who were for the most part unknown. The elite also embraced them, as evidenced by the writings of Ibn Qutaybah and al-Jāḥiẓ, among others.

Every stage in the production of handwritten books was defined by a name which precisely indicated what that stage entailed. All the detailed texts explaining the whole process were held in safekeeping by the top manufacturers to guard the profession's secrets. Long ago, the great calligrapher, Ibn alBawwāb, admitted in a famous poem:

"Do not hold any hope of secrets divulged by me;

I will always withhold its (the profession's) secrets."

In view of these observations and my collection of the old texts mentioned above, I became certain that every branch of the art of book production has its own technical terms, derivatives, and verbs.

I looked again at many published texts, which had been poorly edited and lacked precision in respect of technical terms distorting their true meanings. I therefore started to extract lexical material on the instruments and processes of every age, divided according to the dates of the texts, and quoted documented examples of usage with reference to the source material. This helped to trace the development of the term and how it acquired new connotations that did not exist in the original concept. I also prepared the logical linguistic definitions of these terms and made some headway in the preparation of index cards on which to record anything that I considered useful in the preparation of "A Dictionary of Terms used in the production of Arabic Manuscripts".

The value of this work lies in the fact that it highlights the linguistic and descriptive instruments for dealing with a great and far-reaching art, of which we know little, although its historic relics are among the most important manifestations of the Islamic civilization.

The genius of the Arabic language and its capacity for expansion are evident through the process of 'derivation', one of the most important pillars of linguistic development, and through the forms of the verbal nouns, which were important instruments in forming the variety of terms. The advantage of the verbal noun is that it indicates the event without any reference to its timing. The genius and capacity of Arabic were also evident through the linguistic forms that indicate the name of the instrument, tools, etc.

This dictionary establishes a number of facts and reaches certain conclusions, among them:

- The early Islamic manuscript was a complete art together with its creative tools, language and terms.

- Collecting all relevant texts represents a great contribution in consolidating source materials on the codicology of Islamic manuscripts, and demonstrates continuity of development between earlier and later artistic schools.

- These texts document craft developments which were contemporaneous with, and connected to, the production of Islamic manuscripts.

- The scientific data contained in these texts (especially about paper and ink) will provide researchers and analysts with information about the ingredients of manuscript materials enabling them to take them into consideration when they plan for preservation.

- This dictionary will facilitate the speedy familiarisation of researchers, and analysts with the ingredients of dyes, adhesives and also the pigments contained in inks; thus they will not waste any time in formulating incorrect hypotheses.

- The dictionary's precision in presenting technical terms and chronicling their usage will enable scholars to correct what have now become widespread misreadings in published texts.

In this regard, I should like to point out that other works have been published in other languages of the Islamic world, and elsewhere, in an effort to fix the technical terms used in one or more of the Islamic manuscripts

Most of them fall between the lexicon and the glossary. Among the newest and most important is a Persian dictionary of terms used to describe and classify manuscripts, copies, paper and ink. It was compiled by Najīb Māyil Hiravī under the title Farhang-i vāzhigān-i niẓām-i kitāb-i ārāyī and was published in his large encyclopaedia, Kitāb-i ārāyi dar tamaddun-i Islāmī, Iran: Mashhad (1372) 569-832. In Turkish, we have Mine Esiner Özen's work on the terminology of the binder's craft, Yazma Kitap Sanaltarl Sözlüğü, Istanbul (1985). We also have Denis Muzerelle's French work which is like a dictionary with explanatory figures, Vocabulaire Codicologique: repertoire methodologique des termes Français relatif aux manuscripts, Edition CEMI (1985).

| Source note: This article was published in the following book: The Conservation and Preservation of Islamic Manuscripts, Proceedings of the third conference of Al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation, 18th-19th November 1995 - English version, 1996, Al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation, London, UK, pp. 147-150. Please note that some of the images used in this online version of this article might not be part of the published version of this article within the respective book. |