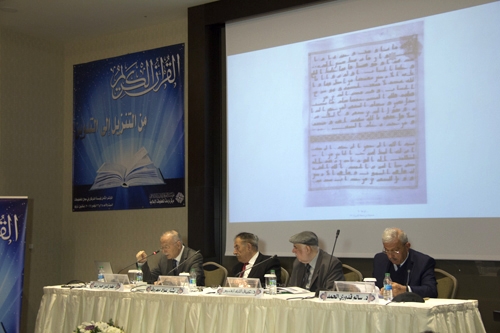

Al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation organised an international conference on the Noble Qur’ān, titled “The Noble Qur’ān from Revelation to Compilation”, which took place in Istanbul, on Saturday and Sunday, 26-27 November 2017CE (8-9 Rabī‘ al-Awwal 1438AH). The conference witnessed a significant scholarly presence, with the participation of thirteen specialist researchers from around the world.

The 8th edition of this conference was held on the backdrop of the 22 July 2015 announcement by Birmingham University that it had performed radiocarbon dating on one of its old Qur’ān manuscripts (popularised in the media as the “Birmingham Qur’ān”). The result had dated the manuscript fragments to the period 568-645CE with an accuracy of 95.4%, i.e. to the first and not the second or third Hijri century as previously thought. The news provoked a tidal wave of contrasting opinion continuing until recently. Indeed, some commentators had inappropriately cited the test results to conclude that the Noble Qur’ān actually preceded the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him. In this context, Al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation decided to convene a conference tackling the subject of manuscript Qur’ān copies. The aim was to introduce and explain the importance of manuscript Qur’ān copies, as well as highlight the need to catalogue, reference, and make these available to researchers. Moreover, to track different projects regarding the publication of these Qur’ān manuscripts, such as the Corpus Coranicum project, and any other matters overlapping with Qur’ānic studies.

The first day of the conference was distinguished by the opening session, followed by three specialised sessions. The opening session began with a recitation from the Noble Qur’ān, then the screening of a documentary film, showcasing the efforts by Al-Furqān Foundation and its various centres in the service of the Islamic heritage. These included organising conferences, cataloguing manuscripts, and releasing critical publications. Subsequently, Mr Sali Shahsivari, Managing Director of Al-Furqān, delivered a speech welcoming the esteemed scholars and researchers participating in the conference. He praised their collaboration with the scientific committee organising this veritable feast of knowledge, while conveying his sincere wishes for an enjoyable stay in the city of Istanbul, and their continued scholarly success. He mentioned that this conference was complementary to previous conferences by Al-Furqān, which had focused on manuscript texts in the different disciplines and spheres of knowledge. Moreover, it fulfilled the wishes of Al-Furqān’s Board of Experts, who had recommended the Foundation’s focus on the Noble Qur’ān, from the phase of Revelation to that of compilation. He then mentioned Al-Furqān’s extensive efforts in the diverse scientific disciplines within its defined areas of interest, noting the continuity in the pioneering and novel organisation of conferences and training courses in different parts of the world. He indicated that this conference was addressing a fine yet thorny issue, relating to the Noble Qur’ān from the phase of Revelation to the phase of compilation. It aimed to refute some of the fallacies that had been propagated at this particular time. Indeed, those issues raised in some orientalist writings, and others of their like.

Following the opening session, Professor Bashar Awwad Marouf chaired the first session, with contributions from three research scholars, namely Dr Omar bin Abdul Ghani Hamdan, Dr Adel Ibrahim Abu Sha’ar, and Dr Ghanim Qaddouri al-Hamad.

Dr Omar bin Abdul Ghani Hamdan presented the first paper titled “The ‘Uthmānī Qur’ān compilation project and the extant disagreement on dates and number of copies”. It represented a new reading aimed at determining the date of the transcribed Qur’ān and number of copies made. He concluded that the transcribed Qur’ān copies had been executed in three phases.

In the first phase, the personal copy belonging to the Grand Caliph ‘Uthmān—peace be upon him—was compiled, followed by copies that were dispatched to those parts of the Muslim world where variant readings were an issue, such as Kufa, Basra, and Damascus; moreover, attempting to determine the number of these copies.

In the second phase, around 30AH, further ‘Uthmānī copies of the Noble Qur’ān were produced. The most credible of opinions notes that there were six copies, which were dispatched to other Muslim territories, such as Makkah, Madinah, Egypt, and Yemen. These territories had not witnessed the issue of variant readings, as was the case in Iraq and the Levant.

The third phase, at 33AH, saw another batch of Qur’ān copies were produced. These were sent to some frontier lands, such as Homs, Tiberias, and Tarsus.

It is perhaps the lack of distinction made between these three phases that led to disagreement and confusion over dates of transcription, and number of copies dispatched to the Muslim territories.

The second paper by Dr Adel Ibrahim Abu Sha’ar was titled “Diacritical marks in manuscript Qur’ān copies: from the first to the end of the fourth Hijri century”. The paper explored the science and methodological foundations of diacritical marking in the orthography of the Noble Qur’ān. It also reviewed the principal diacritics in Qur’ān manuscripts of the Islamic East (Mashriq) and key historical milestones in their development. In addition, it discussed the methodology, colours, phonetic indications, and their role in resolving the phenomena relating to orthographic features (al-rasm), authentic vocal rendition (al-tajwīd), canonical readings (al-qirā’āt), and prevention of misreading (al-taṣḥīf) and metathesis (al-taḥrīf).

On his part, Dr Ghanim Qaddouri al-Hamad presented his paper, “Qur’ānic readings in pointed Qur’ān copies dating back to the primary three centuries”. He noted that the diacritical marking method in these Qur’ān copies was not consistent with any of the seven or ten canonical readings that had been elucidated in the era of Ibn Mujāhid (d. 324AH) and his students. He demonstrated through irrefutable evidence, the baselessness of the opinion that states that any reading that disagrees with these seven or ten canonical readings is considered non-canonical (shādhah).

The session was distinguished by fruitful scholarly discussion, concentrated mainly on the necessity of distinguishing between the compilation of the Noble Qur’ān during the time of Abū Bakr al-Ṣiddīq and its copying in the time of ‘Uthmān b. ‘Affān. In addition, the discussion emphasised the need to study the chain of narrators (isnād) related to those traditions (āthār) describing that phase, and determining their degree of authenticity, in order to draw the correct conclusions.

The first evening session was presided over by Dr Ghanim Qaddouri al-Hamad, in which three research papers were presented.

The first paper by Dr Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu followed the journey of “The Qur’ān attributed to the Righteously-Guided Caliph, ‘Uthmān b. ‘Affān, preserved in Topkapi Palace, through historical and codicological observations”. In the paper, he concluded that this Qur’ān is not one of the early copies sent to the Muslim territories, due to the quality of calligraphy and diacritics, in addition to the decoration contained. He also explored the efforts made to publish it, which represented an important episode in the study of the history of the Noble Qur’ān.

The second paper titled, “The effect of the licence of the seven letters on the transcription of the Qur’ānic text” was presented by Dr Salim Qaduri al-Hamad. In his submission, he explored the extent of the effect of the licence of the seven letters in the transcription of the Noble Qur’ān during the Prophet’s time, and then the subsequent Caliph, Abū Bakr al-Ṣiddīq. He then elucidated its effect on ‘Uthmānī orthography.

The third lecture was titled “Insights into the Prophetic tradition {This Qur’ān was sent down in seven letters}”. Dr Bashar Awwad Marouf followed up the variant narrations of this tradition. He explored the differences among scholars regarding its meaning, whether the matter related to seven readings, seven regions, seven [Arabic] dialects, or seven similar meanings worded differently. After weighing these up, he elected the last one as being the most credible. He then proceeded to explain that the Noble Qur’ān had been compiled in the time of Abū Bakr al-Ṣiddīq, then further copies were made in the time of Caliph Imām ‘Uthmān b. ‘Affān, based on one letter (ḥarf); all other copies that differed with this, were abrogated, some of which came to be considered non-canonical readings (shādhdhah).

The session was followed by a number of discussions and scientific responses, mostly concentrating on the necessity to re-read the authenticated (ṣaḥīḥ) traditions (āthār) describing that phase.

The second evening session was chaired by Dr Abdallah al-Ghunaim, where three papers were presented.

The first titled, “Verbal transmission of the Noble Qur’ān and the methodology of historical criticism” was delivered by Dr Abdul Hakim b. Yusuf al-Khalifi. In his paper, he attempted to explain that vocal transmission had not been the sole way for preservation of the Noble Qur’ān, rather writing also played a key role. He demonstrated the error of the opinion that considers it a necessity to apply the methodologies of historical criticism to the Noble Qur’ān, as was applied to Bible texts, in both Old and New Testaments.

The second paper, “History of the Noble Qur’ān from verbal to written: a critical, codicological study of the Orientalist school”, was presented by Dr Karim Ifraq Ahmad. In the paper, he recalled the numerous attempts by the Orientalist school to promote distortions and misrepresentation about Islam generally, and the Noble Qur’ān in particular. He noted the absence of robust scientific responses to these misrepresentations and emphasised the necessity for scientific responses, by those within their area of specialisation.

The third paper was by Dr Sami Mohamed Saeed Abdul Shakur, titled “Canonical readings from the time of inception to the age of Ibn Mujahid, and refuting the misconceptions raised by Dr François Deroche”. In the paper, Dr Sami followed those attempts by Deroche to discredit the transcription of the Noble Qur’ān, and the vital importance of referring to those readings that were discarded after that phase. He also attempted to refute Deroche’s misleading notions.

The second day witnessed two sessions.

The first session was chaired by Mr Sali Shasivari, with the participation of three scholars, namely Dr Abdul Razak bin Ismail Harmas, Dr Abdallah al-Khatib, and Dr Qasim al-Samarrai.

Dr Abdul Razak b. Ismail Harmas presented his paper titled “The critical commentaries of the Noble Qur’ān at the dawn of the Corpus Coranicum project”. In his submission, he mentioned the historical phases of the Corpus Coranicum project, and its most prominent protagonists, aiming to create a copy of the Noble Qur’ān that was in circulation before it was collated and transcribed.

The second paper was presented by Dr Abdallah al-Kahtib, titled “Orientalist readings of the Noble Qur’ān: the example of the Corpus Coranicum project”. In his paper, he addressed some of the Orientalists’ slanders projected on the Noble Qur’ān prior to, and during this project. He mentioned this project’s origins, historical phases, aims to be achieved, and suggested means to respond to it, concluding the paper with his recommendations.

The third paper, presented by Dr Qasim Al-Samarrai, was titled “Accuracy of C14 carbon testing in dating of Qur’ānic parchment, and its relationship to palimpsests”. In his paper, he sought to prove the accuracy of radiation dating of old Qur’ān parchment, using C14 radiocarbon analytical technology, compared to traditional methods that were standard in dating such parchment.

The session was followed by a discussion mainly around the weak Islamic scholarly responses to Orientalist studies of the Noble Qur’ān.

The evening session was chaired by Mr Mohamed Drioueche, and was distinguished by the lecture delivered by Dr Idham Mohammed Hanash, titled “The aesthetic approach to studying manuscript Qur’ān copies”. In his submission, he studied the aesthetic and artistic aspects relating to the Noble Qur’ān, principally calligraphy and diacritics.

The lecture was followed by an open session with Dr Bashar Awwad Marouf and Dr Ghanim Qaddouri al-Hamad.

In his talk, Dr Bashar Awwad Marouf emphasised that the Noble Qur’ān had been transcribed in full in the time of Abū Bakr al-Ṣiddīq, in the aftermath of the Battle of Yamamah, where many memorisers (ḥufāẓ) had been martyred. This work was undertaken under the supervision of the eminent Companion, Zayd b. Abī Thābit—an intelligent young man, who moreover had the Qur’ān committed to memory; he was now entrusted with its gathering / compiling. Henceforth, Zayd began to seek out and gather the Qur’ān as written on palm branches, white stone, and bone, as well as from individuals’ memory.

In the time of Caliph ‘Uthmān, Zayd copied what he had collected in Abū Bakr’s time into master copies (umahāt), which were then distributed to the Muslim territories. Professor Awwad drew attention to the importance of qualifying this phase with the word “copying”, and not gathering / compiling the Qur’ān; this is because the latter gives the impression that the Noble Qur’ān was only captured in writing 20 years after the death of the Messenger—peace be upon him, which is patently not correct. He added that ‘Uthmān’s initiative was successful, and that thousands of Qur’ān copies were made. Indeed, al-Ḥāfiẓ al-Dhahabī (d. 748AH) mentions the existence of over two million copies of the ‘Uthmānī muṣḥaf in his time. Professor Awwad concluded his talk by pointing to the fact that campaigns aimed at discrediting the Qur’ān were not new, but as old as Islam itself. He emphasised the necessity of avoiding populist, media-focused responses. Indeed, academic journals, conferences, and discussions reinforced by knowledge and evidence were the ideal way of presenting these responses.

On his part, Dr Ghanim Qaddouri al-Hamad praised the papers presented, and emphasised the necessity of giving old manuscript Qur’ān copies due attention by way of research and examination. He illustrated that the researcher of the Qur’ān draws on five essential sciences associated with the Qur’ān, namely orthography, diacritics, canonical and non-canonical readings, pause and beginning (al-waqf wa al-ibtidā’), and number of verses. He mentioned that over forty years ago, when he wanted to view the manuscript Qur’ān held at Jāmi‘ al-Ḥusayn attributed to ‘Uthmān b. ‘Affān for his thesis on Qur’ān orthography, he was forbidden from doing so. All manner of petitions or letters were to no avail in changing this draconian position. However, today, due to the revolution in digitising and publishing manuscripts, this and other copies of the Qur’ān were now available to researchers. Dr Al-Hamad drew attention to the fact that “each manuscriptQur’ān copy possesses intrinsic scientific value, because it represents a specific phase of the history of themuṣḥaf’s long journey; tended by scholars, calligraphers, decorators, and memorisers, until this copy was executed; hence, each Qur’ān copy possesses scientific value in its study”. Dr Al-Hamad mentioned that he had gathered new studies on manuscript Qur’ān copies in two of his books. The first he had titled “’Ilm al-maṣāḥif” and the second, “’Ulūm al-Qur’ān bayn al-maṣādir wa al-maṣāḥif”. He stressed the importance that public bodies and organisations in the Muslim world should gather and catalogue manuscript Qur’ān copies, and provide access to researchers and learners. Moreover, holding exhibitions on the Qur’ān and publishing journals that address this area of research. Dr Al-Hamad concluded his talk by emphasising the importance of translating the latest studies on the area of manuscript Qur’ān copies into Arabic. He thanked Al-Furqān for laying the primary foundations of this project by organising this conference, while anticipating that it be followed by further conferences dedicated to studying the critical scientific issues raised at this conference.

This was followed by the closing speech delivered by Mr Mohamed Drioueche, in which he thanked the conference participants, followed by reading out the recommendations and recitation of verses of the Noble Qur’ān.

Conference recommendations

The conference delivered the following recommendations:

1. Al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation to publish the conference papers widely, especially within specialised scientific circles, and work to translate these into foreign languages.

2. Al-Furqān to adopt a project attending to manuscript Qur’ān copies (maṣāḥif), and supporting and encouraging scientific research projects in this area. Also, establishing a dedicated website to promote such studies, and preparing a comprehensive bibliography of Qur’ānic studies, whether from the West or East, and making these available on a database.

3. Establishing a scientific centre specialising in the history of manuscript Qur’ān copies, parallel to the “Corpus Coranicum” project, under the auspices of Al-Furqān Foundation. This would establish strong links with museums, and libraries worldwide, and attempt to gather the early Qur’ān copies in digital form. These must be catalogued in scientific, analysed form, and made available to researchers and learners.

4. Organising international scientific conferences, symposia, and training courses in the area of manuscript Qur’ān copies, and promoting their scientific, historical, and aesthetic value, while following orientalist efforts around the Qur’ānic text; all under the umbrella of scientific bodies and centres that assure a wide following from researchers and learners.

5. Coordinating Al-Furqān’s efforts with those of other scientific establishments working in the same area (such as Markaz Tafsīr al-Dirāsāt al-Qur’āniyyah in Riyadh) to enhance the level of these studies. Furthermore, organising a second conference on this topic, and examining other areas not addressed in this conference.

6. Studying the foreign language dictionaries, encyclopaedia, and research papers relating to the Noble Qur’ān, and responding to those misrepresentations contrary to the consensus of the Muslim nation, through objective, robust scientific responses.

7. Al-Furqān Foundation to work at publishing a book or reference on the history of the Noble Qur’ān from the Islamic perspective, and to translate it into foreign languages. The text should address the Western mentality, and place the truthful rendition of this history at their disposal.

8. Publishing a scientific encyclopaedia specialised in the sciences of the Noble Qur’ān, and translating it into foreign languages, in order to enlighten the world of the Islamic view on issues relating to the Noble Qur’ān.

Related Video

From Bangladesh. Can you publish this book in English?

Dear Mr Thanvee, Thank you for your comment. We have passed it on to our Projects and Publications department.

Dear Mr Thanvee,

Al-Furqān Foundation plans to translate selected papers from the proceedings of this Conference, after the third part of this Conference, which will be held next year.

I will wait for that. Please let me know via email or any other means whenever it will publish.