François Déroche, with contributions by Annie Berthier, Marie-Geneviève Guesdon, Bernard Guineau, Francis Richard, Annie Vernay-Nouri, Jean Vezin, Muhammad Isa Waley

Theoretical approach

The field of application

Alongside the analysis of the material conditions of the production of manuscript books, another function of codicology is to establish the history of libraries and collections:[1] that is, to gather data on how books circulated after they were made, reconstructing as far as possible the chain of owners of a manuscript or set of manuscripts, and determining the provenance or places where the volumes were kept.[2] These questions directly concern Oriental manuscripts-especially those in Arabic, Persian, and Turkish-in public and private libraries and collections in both East and West.

The need for a history of collections: a multidisciplinary field

The history of collections is part of a broad field of scholarly endeavour. By progressively reconstructing the history of a volume or set of volumes, by seeking to learn which text (or group of texts) entered and became known in, say, France-along with when and by whom, and based on which copies-codicology can provide keys to the history of ideas and their dissemination, to the inter-relationship of cultures, and to a better knowledge of Oriental studies in Europe and of the heritage of the Oriental countries involved.[3] Such research also concerns the history of texts insofar as documenting the location of a copy in a given place or in the collection of an identified scholar helps to trace the history of transmission of the text itself, which may have been used as the basis for another copy, a translation or even a printed version. Furthermore, the history of manuscripts also involves art historians, curators, historians, numismatists, historians of literature, linguists, philologists and even legal scholars.

The special nature of Oriental manuscripts held in Europe

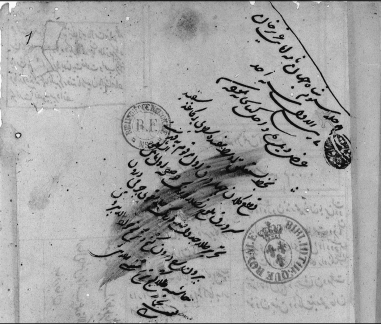

The physical nature of Oriental manuscripts held in Europe is characterised by the fact that marks, alterations and restorations of text or changes in binding may have a double origin - Eastern or Western -testifying to their itinerant background. In studying such manuscripts, scholars encounter problems relating to both Eastern and Western codicology, and they must therefore be competent in multiple fields, including a familiarity with all the key reference works. Deciphering and identifying various collating marks, both Oriental and Western, might at first sight seem to depend on highly specialised analyses, given the languages and scripts involved, yet in fact such tasks are closely interrelated and the problems to be solved are highly similar from a methodological and technical standpoint.[4] Moreover, although some Oriental volumes now in Europe have undergone significant alterations (change of covering, for instance), a good many have retained their original appearance, which means that studying them can directly contribute to the history of Oriental manuscripts; indeed, in Eastern lands the various conservation measures applied to manuscripts down through the ages have often considerably altered their appearance if not their Oriental nature. Since Oriental collections in Europe and the East do not share the same history, the analytical methods employed when examining them must be adapted to their specificities.[5]

What constitutes an Oriental manuscript?

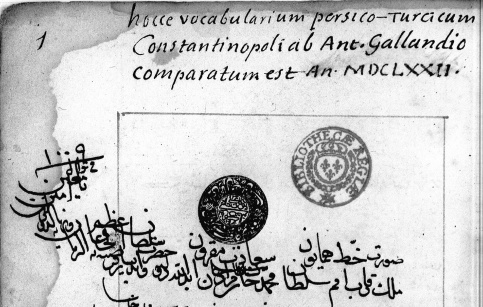

The concept of Oriental manuscript obviously covers books produced by Orientals in the Orient for their own use, as is the case with most volumes, yet also those produced for use by Westerners in a form that might often be adapted to their specific use.[6] The notion of Oriental manuscript also extends to books written in Arabic script by Europeans, constituting the special field of Western Orientalist codicology. For instance, the so-called ‘translations collection’ in the Oriental Section of the Manuscript Department at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France comprises Oriental-style volumes produced in the early eighteenth century by the ‘jeunes de langues’, young students who received scholarships from the French government to study interpreting in Constantinople; an Ottoman Turkish text with a French translation would be bound into a single volume with fore-edge flap and envelop flap.[7] Furthermore, manuscripts in Arabic script were sometimes produced in Europe by Orientals who were temporary or permanent residents there, as exemplified by a version of the New Testament copied in Paris by the Syrian Ḥannā Shāmī in ɪ680 (MS. BNF suppl. turc ɪ -2 and 3), based on a Turkish translation of the Gospels printed in Oxford in ɪ666. Finally, there are the grammar books and dictionaries written by Westemers either in Paris or on their travels to the Orient.[8]

The history of collections and the current state of cataloguing

The emergence and development of codicological knowledge has had a major impact on the organisation of catalogues of manuscripts, which is why the subject is addressed here. Broadly speaking, it became essential to revise the old catalogues compiled in the West due to the need for an exhaustive material description of each item. A catalogue entry could no longer overlook any of the elements that might contribute to the establishment of an increasingly accurate history of the document, which meant giving, in chronological order, all useful information on the libraries and collections in which it figured. This revision also entailed the standardisation of entries - at least on a European level - as well as the regular updating of relevant literature. In addition to correcting putative errors and inaccuracies, one of the roles of descriptive entries in the new catalogues is to provide information on the history of the volume and its peregrinations, the new catalogues are also designed to contribute to the filing of all this data in abstracts based on the systematic organisation of entries and the production of summary tables. Generally speaking, the new generation of catalogues integrate new data as a function of new categorisations that each require appropriate resources.

A manuscript entry is always a reflection of immediate needs - it is a functional item that mirrors the general scholarly trend of each period. In Europe, beginning in the eighteenth century, the appearance of the notion of scientific investigation and the systematisation of knowledge influenced the constitution of catalogues, which became increasingly exhaustive and increasingly accurate; ‘observe’ and ‘measure’ were the two watchwords of a man like the Comte de Volney, the eighteenth-century promoter of cultural research and of a system for transliterating Oriental languages. Specialised fields, notably the scientific study of the Orient, emerged in the nineteenth century shortly after the invention of the metric system, whose general adoption, it should be recalled, dates back just ɪ20 years. To take a French example, the first volume of Catalogus Manuscriptorum Bibliothecae Regiae (Catalogue of manuscripts in the Royal Library), published in ɪ739, was entirely devoted to Oriental manuscripts and featured entries that were extremely brief yet contained all the main ‘ingredients’[9] found in modern descriptive catalogues: not only author and title but also type of support, format, and provenance[10]; previously, any indications of the contents of a manuscript, written in French or Latin, had often been placed in the book itself, on either the inner cover or the flyleaf (illus. 114a). Sometimes the entry would be printed on a little piece of paper glued to the inner cover; nineteenth-century catalogues such as the one compiled by MacGuckin de Slane, were written in French but used Arabic letters for the titles of books in both entry and index, and details concerning the history of the volume were somewhat fuller.[11] Modern catalogues - from the early twentieth century to the present - exhibit impressive progress in the amount of codicological information provided as well as in its classification.[12] Computerisation of catalogues, now making major strides in terms of the use of original alphabets and their transliteration, as well as digitised images, should be of considerable benefit to codicology in general and to the history of collections in particular.[13]

Writing the history of collections of Oriental manuscripts

Methods

A rigorous methodology and various material tools now enable codicologists to conduct an investigation that should provide a maximum number of clues for establishing the most complete possible history of a volume.[14]

The history of a volume or set of volumes should be based on several observations: examination of marks made on the books (see illus. 155-158), which must be identified and/or compared with other similar marks found elsewhere, in order to constitute groups and to establish, as far as possible, a chronological classification, examination of the binding and any potential alterations; examination of modifications of all kinds in every part of the volume. In accomplishing these tasks, two things are imperative: knowing, as thoroughly as possible, the collection on which one is working and, if possible, other related or similar collections; understanding and assembling - indeed, designing - the right tools for the job.

The distinctive features of a manuscript...

*The remainder of this article is exclusively available in the printed version of the related book. The book is available in both electronic and printed formats within Our Publications in the following link:

http://doi.org/10.56656/100099

[1] ‘Library’ is used here in the general sense of an organised assortment of books held either by a public institution or private individual, while ‘collection’ refers to a particular group. Thus ‘the history of collections’ refers to sets of manuscripts and documents artificially united on the basis of shared features (language, subject matter, etc.); a collection might be assembled from a variety of sources and is generally held by an institution, whether public or private.

[2] Charles Samaran’s L’Histoire et ses méthodes (Paris, 1961) refers to a field of study ‘of sets of manuscripts having a shared origin or history, which mutually explain one another.’ Samaran closely relates this field to codicology, ‘which, for lack of a better term, will be called the “archivistics” of manuscripts.’ Nowadays the term ‘history of collections’ is more appropriate.

[3] See Annie Berthier, ‘Manuscrits orientaux et connaissance de l’Orient, éléments pour une enquête culturelle’, Moyen-Orient et Océan indien, XVIe-XIXes. 2, 2 (1985), pp. 79-108, and Berthier, ‘Collections de manuscrits et genèse des études orientales en France’, Reυue arabe d’archives, de documentation et d’information 1-2 (May 1997), pp. 9–19. See also many publications by F. Richard, notably ‘Jean-Baptiste Gentil collectionneur de manuscrits persans’, Dix-huitième siècle 28 (1996), pp. 91–110.

[4] See the ‘Introduction’.

[5] See Annie Berthier, ‘Contribution à l'histoire des fonds de manuscrits orientaux des bibliothèques européennes, le Fonds turc de la Bibliothèque nationale de Paris’, Mss du MO, pp. 17-22. As far as France is concerned, the Bibliothèque royale’s first printed catalogue, published in 1739, listed 7,000 Oriental volumes, a majority of which were Chinese, followed, in order of number, by Arabic, Persian, Turkish, Hebrew, Indian, Armenian, Syriac, Coptic, Samaritan and Ethiopian manuscripts, all of which then comprised nearly 5% of the total library (manuscripts and printed volumes combined). Today, over 30,000 Oriental manuscripts in eighty languages, divided into sixty specialised collections, are held at the Rue Richelieu site of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, of which 11,800 volumes are in Arabic, Persian, or Turkish. The founding of collections of Oriental books in France, notably at the Bibliothèque royale, occurred in the context of developments triggered by the ‘age of exploration’, both geographical and technological. Handwritten inventories of the Oriental collection in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, with reference to their acquisition, by purchase or bequest, are dispersed throughout the French and Latin collections. Starting in the late eighteenth century and throughout the nineteenth, projects were undertaken to catalogue and list documents of all kinds, as were programmes for translation and cultural exchange. The impetus given by the Académie des inscriptions et belles-lettres was paramount, for a decision was taken in 1786 to establish the famous collection of ‘Notices and extraits des manuscrits’ stressing the importance accorded to the ‘knowledge of men and events, times and countries, habits and customs, laws, arts, sciences, and literatures of all nations.’ In the May- June 1855 issue of the ɉournal Asiatique, Joseph-Toussaint Reinaud published an outline of his plan for cataloguing the entire Oriental collection of France’s national library, setting new standards for scholarship. It was in this context that Mac Guckin de Slane published the catalogue of Arabic manuscripts. Efforts continued until the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, which considerably delayed work and deprived scholarship of a great number of researchers, a situation that recurred during the Second World War. A new push was made after 1945, fresh impetus being given by the publication of catalogues by Vajda, an effort that has been sustained into the recent past. The cataloguing programme is now embarking on a new phase of its history, inextricably linked to the development of new technologies.

[6] See Annie Berthier, ‘Le fonds turc du Département des Manuscrits’, Bulletin de la Bibliothèque Nationale VI (June 1981), pp. 78-95.

[7] See Annie Berthier, ‘Turquerie ou turcologie? L’effort de traduction des Jeunes de langues au XVIIIe siècle d’après la collection de manuscrits conservée à la Bibliothèque nationale de France’, in F. Hitzel (ed.), Istanbul et les langues orientales. Actes du colloque organisé par l’IFEA et l’INALCO à l’occasion du bicentenaire de l’Ecole des Langues orientales, Istanbul 29-31 May 1995 (Paris, 1997), pp. 283–317.

[8] See Annie Berthier, ‘A l’origine de l’étude de la langue turque en France: liste des grammaires et des dictionnaires manuscrits du fonds turc de la Bibliothèque nationale de Paris’, Mélanges offerts à Louis Bazin (Varia Turcica, XIX], 1992, pp. 77–82.

[9] In European catalogues, manuscript shelf-marks, initially based on the location of the volumes on the shelves, evolved toward a more theoretical system. Entries giving the author’s name were generally fairly approximate, as regards both precise identification and transliteration; for the same reasons, many titles would remain vague. Often, all that was indicated was the type of book, the nature of the writing surface (paper, parchment, etc.) sometimes being the only identifying feature provided. Provenance was frequently noted, for example, ‘recently purchased in Constantinople’. The language used for entries evolved from Latin to French, while the use of the original alphabet for entering various elements, notably author and title, was a further interesting factor: in the days when catalogues were handwritten, it is possible to find title entries still employing the alphabet of the original language, whereas with the advent of printing there was a sudden rise in approximate transliterations, which only became more accurate with Volney’s catalogue and with the development of Oriental typefaces by the Imprimerie Nationale in France (despite the earlier efforts of Savary de Brèves in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries). Reference to relevant literature is a very late innovation in catalogue entries.

[10] Catalogus codicum manuscriptorum Bibliothecae regiae (Paris, 1739).

[11] W. MacGuckin de Slane, Catalogue des manuscrits arabes (Paris, 1883-1895).

[12] E. Blochet, Catalogue des manuscrits arabes des nouυelles acquisitions: 1884-1924 (Paris, 1925). Blochet, Catalogue des manuscrits persans... (Paris, 1905-1934). Blochet, Catalogue des manuscrits turcs... (Paris, 1932-1933). G. Vajda and Y. Sauvan, Catalogue des manuscrits arabes... (Paris, 1978-1985).

[13] See below.

[14] In particular, see the many publications by Gilbert Ouy, and more generally the publications in recent decades on Greek and Latin codicology.

| Source note: This article was published in the following book: Islamic Codicology: An Introduction to the Study of Manuscripts in Arabic Script _ English version, 2005, Al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation, London, UK, pp. 345-361. |