François Déroche, with contributions by Annie Berthier, Marie-Geneviève Guesdon, Bernard Guineau, Francis Richard, Annie Vernay-Nouri, Jean Vezin, Muhammad Isa Waley

Manuscript: the first appearance of this term as a noun in the late sixteenth century - in English as well as in French - indicates that its existence is due in part to the invention of printing. It was only when books were no longer all copied by hand, as the traditional mode of making them was giving way to this irresistible rival, that a new word entered the language: manuscript, a book ‘manually inscribed’, written by hand. And it is books that are the subject of this volume. Of course, in many other contexts, ranging from administrative documents to literary composition, the hand continued to favour the pen and was not to abandon it until long after the sixteenth century. This, however, applies not to books but to documents, whose study falls within the domains of papyrology, diplomatics, and so on. Similarly beyond the scope of this study are inscriptions, even though some of them record texts that also appear in manuscripts or were executed with implements similar to those used by scribes. It is the book, copied by hand for centuries - and more precisely a specific form of book, the ‘codex’ - that is the focus of the field of codicology.

What is codicology? It is a recent term that has its origin in scholarship.[1] A definition ‘that sticks close to the etymological roots would be ‘the study or knowledge of codices’ (from the Latin codex and the Greek λóγoϛ). This answer, however, is too brief and needs to be expanded upon. The field that has adopted the name of ‘codicology’ can arguably claim a certain legitimacy from the way in which the West traditionally referred to books. Unlike Arabic, which places the emphasis on the aspect of writing (in words such as kitāb and makhṭūṭ), English, following French and Latin, etymologically refers above all to materials: ‘book’, ‘codex’, and ‘volume’ derive respectively from words meaning ‘beech tree’, ‘wooden tablet’, and ‘roll of papyrus’. Codicology, then, refers primarily to the study of the material aspects of codices: that is, manuscript books comprising a series of gatherings, or quires, of sheets. This remains the basic structure of the book to this day, even though the printing press has replaced the hand of the copyist.

Not all books are codices

Before going further into the subject, it is worth remembering that books can also be made in other ways. The υolumen, or scroll, long enjoyed a dominant position in the Mediterranean world.[2] Nor did the triumph of the codex banish every other form of book. True enough; manuscripts in the form of υolumina did not play a major role, numerically speaking, in the Arab and Islamic world.[3] By the time Islam appeared, the Mediterranean world and surrounding regions had replaced scrolls by codices. Volumina did survive in vestigial form, thanks to the liturgical use made of them by Jewish communities - in the form of Torah scrolls-which Muhammad and his followers certainly knew of.[4] But when the text of the Revelation came to be compiled into a book, it was the dominant form of the book - the codex - that was employed.

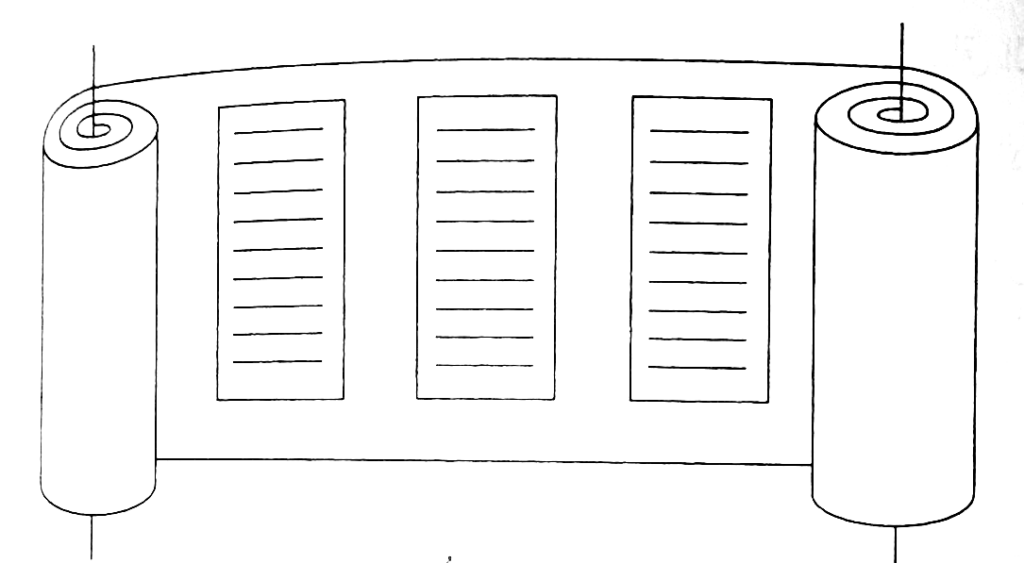

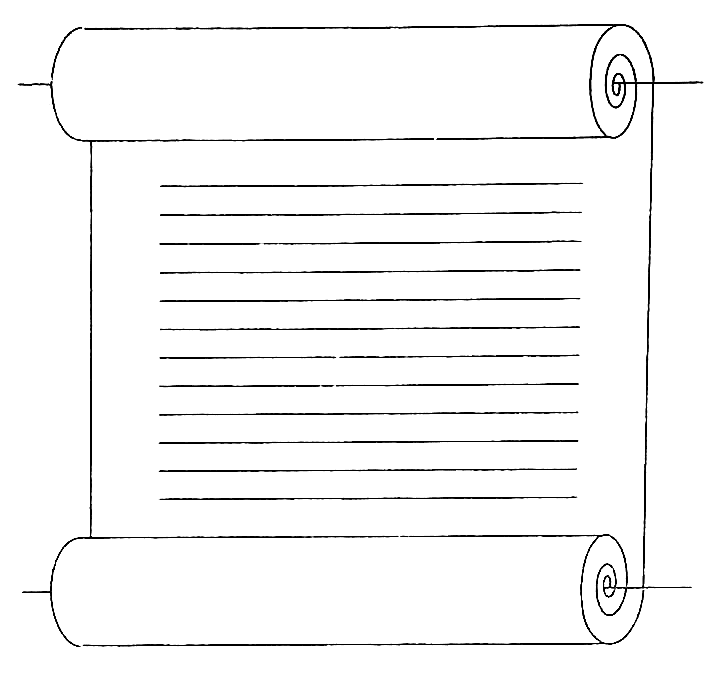

Volumen and rotulus

It appears that Muslim scribes never used the υolumen, a form characterised by the layout of text in lines perpendicular to the axis of the scroll, arranged in a series of columns read one after another (see illus. 1). The only Islamic manuscripts in the shape of rolls that have so far come to light are in the form of a rotulus (illus. 2). In this latter case, the text runs parallel to the axis[5]; calligraphic variations on this form are not unknown, most of them being copies of the Qur’ān, but such exceptions are few and wholly untypical. To conclude this brief discussion of scrolls, a form that is peculiar to Indonesia deserves to be mentioned. It consists of long, narrow strips of palm stitched end to end, along which runs a single line of text; a wooden or metal frame holds its two rolls together side by side (MS. Jakarta Perpustakaan Nasional, Vt. 43).[6]

Accordion-fold books

Other manuscripts may look like a codex from the outside, but their form is based on a different structure, one that does not use quires of sheets. Most people who have studied calligraphy or miniatures will have come across folding albums pleated like an accordion.[7] They are composed of pieces of pasteboard, to which a series of miniature paintings or pieces of calligraphy have been affixed, held together by flexible cloth hinges. Many accordion-style manuscripts of this type are anthologies put together by a third person - the collector - who brought together items of diverse origin as he saw fit. Another distinctive form, found in certain manuscripts from sub-Saharan Africa, is made up of individual sheets held together by a binding.[8] These will be discussed later.

Single-sheet manuscripts

Manuscripts in the single-sheet format - that is, wherein each leaf corresponds to an individual sheet[9] - were produced mainly during the early Islamic period. The few surviving examples were copied on parchment and make it easy to understand how they were made. Not a single specimen, unfortunately, has come down to us in its original binding, so that it is impossible to know how the sheets were originally held together. A typical example is MS. BNF arabe 324, which can be dated to the latter half of the second/eighth century.[10] Initial examination shows that the flesh side of the parchment most often serves as the recto.[11] Two series of leaves - folios 18 to 27 and 30 to 37 - contain continuous texts, one of ten leaves, the other of eight. In accordance with the usual practice (to be discussed later), the flesh side of the parchment is used for the recto, except for folio 23, which is reversed. It might be thought that these are vestiges of gatherings of sixteen or twenty leaves; but another explanation seems preferable in the light of a study of the 122 leaves of a Qur’ānic text found in two Istanbul manuscripts (TIEM 51 and 52), whose hand is similar to that of the Paris fragments and which present a continuous series of flesh sides as the rectos.[12] Both examples are single-sheet manuscripts, and since each of their leaves represents an entire skin there is no fold, so that the text block is not

made up of gatherings. The leaves all face the same direction; that is to say, all the rectos employ the flesh sides of the parchment, while all the versos are hair sides. The state of these manuscripts, which have clearly undergone repeated restoration, makes it impossible to determine how the leaves were originally held together. The question as to whether they were stitched flat[13] or mounted on a stub remains unanswered. TheṢan‘ā’ manuscript (Dār al-Makhțūtāt 20–33. I) may also have been made of single sheets, though it is not clear whether the leaves all face the same way[14] - as of this writing, there is no precise information on this point. Was this approach ever adopted for manuscripts written on paper? We cannot exclude the possibility that Qur’āns of very large size, such as the so-called Baysunghur Qur’ān, each folio of which today measures I77 X I00 cm, may have been made of single sheets.[15]

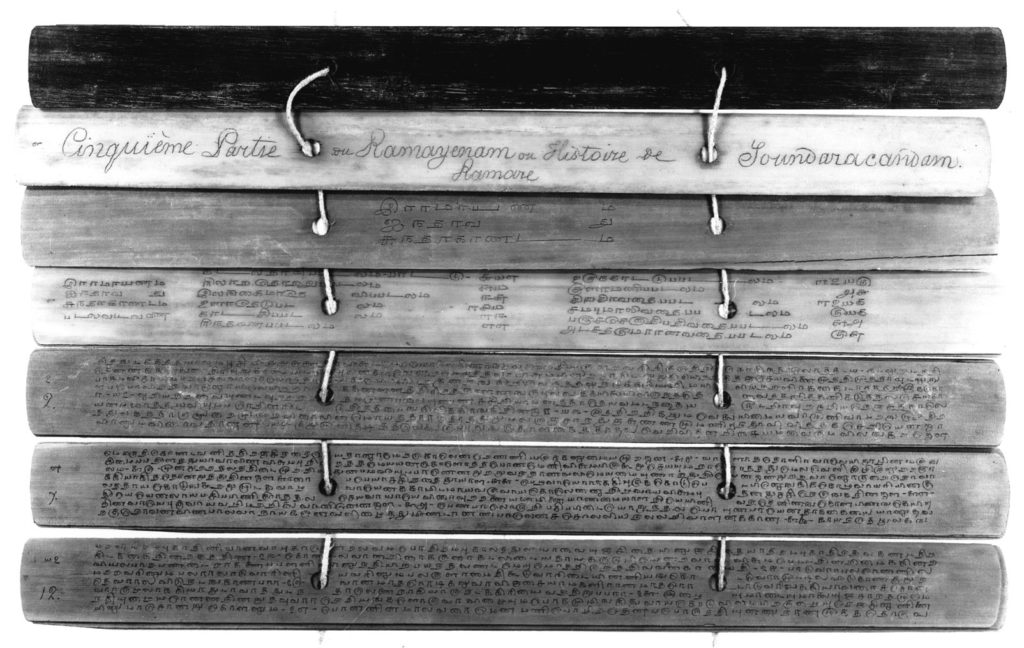

The expansion of Islam soon brought Arab conquerors into contact with other civilisations in which book manufacture had followed a different path. The repercussions of the encounter with the Chinese at the battle of Talas (CE 751) are well-known as the story goes, the capture of papermakers slowly led scribes throughout the Islamic world to adopt paper for copying manuscripts.[16] By contrast, there was no such adoption of the form of books typically used in China. Nor did relations with the Indian subcontinent have much impact on Arab and/or Islamic books: for example, the use of palm-leaf slats called olla (illus. 3) continued to be confined to the indigenous manuscript tradition, since Muslims employed strips of palm leaves only in very special instances, as mentioned above.

The role of codicology in studying manuscripts

The focus of the codicologist’s concern, then, is the codex (illus. 4). This field of study is of relatively recent origin, and is explained by the growing awareness in the twentieth century of the intrinsic interest of books, notably as regards their history. As research has shown, history is quite distinct from that of the texts found in books, whether printed or handwritten. Far from being identical with textual history, codicology sheds light on the history of the period in which a book was produced.

The goals of codicology

To attain its aims, codicology has to undertake two principal tasks. It must first attempt to analyse, as precisely as possible, all the techniques used in making a manuscript. In this task, laboratory methods can solve problems which visual examination alone cannot hope to, for example in determining the

composition of the colours used or identifying the fibres in a paper.[17] Even without the aid of laboratory measuring instruments, however, codicologists can gather a significant amount of data by relying on two stalwart allies - their patience and their curiosity. It is hoped that they will also find this handbook useful, designed as it is to provide readers with clues to enable them to recognise the methods employed by the craftsmen who made the books under discussion.

Such analysis, however, cannot be an end in itself. It should be accompanied by an effort to date the various techniques and even to pinpoint them geographically. All work in this field therefore faces the crucial need to constitute coherent sets of documents that shed light on one another. Some of these documents are dated, and now and then they contain evidence as to their origin; and such manuscripts therefore play an essential role in establishing the comparisons required for codicology to progress. More than anything else, it is the single object taken alone-in the eyes of the person examining it, at least - that is fraught with the risk of error and misinterpretation. And there are many manuscripts for which we have no parallels, at least in the present state of research. These manuscripts are not necessarily unica - unique examples of a text - but are often copies of well-known works, starting with the Qur’ān, which display particularities that are hard to explain given the absence of parallels. For example, the comments made by Jacques Berque concerning a Qur’ān (MS. Tunis Bibliothèque nationale 14.246) are debatable because Berque analysed this copy in isolation,[18] whereas in fact it belongs to a larger group.[19] Of the hundreds of thousands of extant manuscripts in Arabic script, the vast majority have not been adequately studied; many, indeed, remain simply unknown. In order to grasp the limitations of our present knowledge, one need only consider the changes in our understanding of the early centuries of Islam brought about by the discovery of the Qur’ān manuscripts of San‘ā’.[20] Redoubled efforts are therefore required if we are to fully grasp the Arab and Islamic heritage in all its diversity. For the moment, our vision of it is far too incomplete; indeed, it is a limitation of the present handbook that it inevitably reflects the immature state of scholarship in this field, and therefore can represent no more than an initial step.

Codicology and palaeography

Among the various processes involved in producing a manuscript, writing takes pride of place. Specialists in Western manuscripts traditionally accord special importance to the study of writing, or palaeography, which emerged and developed extensively as a science well before codicology appeared, thereby establishing an independent discipline.[21] In the Arab and Islamic field, however, a number of factors impeded the serious study of book scripts, delaying the commencement of rigorous analysis of their forms and evolution. It would thus seem reasonable to include the study of these scripts within the discipline of codicology, which in no way means that we consider manuscript hands to be entirely unrelated to those used for Arabic inscriptions or papyri.

Toward a history of books in Arabic script

The other direction in which codicology must progress remains, for the moment, a distant ideal: the data that specialists are patiently assembling should provide material for a future reconstruction of the history of manuscript books written in Arabic script, faithfully reflecting the intellectual, social, economic, and even technical conditions under which they were produced. Scholars have sometimes directed their research toward more specific goals; Rudolf Sellheim, in Materialen zur arabischen Literaturgeschichte, favours examination of the numerous notes that appear on manuscripts and also accords a larger role to the study of the history of the text, thereby tending to place codicological research more at the service of the history of literature.[22] This latter can in turn shed light on codicology, for example by pointing to the existence of ‘families’ of manuscripts - in other words, groups of copies that derive from a single prototype, often of distant origin.

Codicology and cataloguing

Although the role of codicology makes it an ancillary field of history, its role cannot be reduced to one of merely gleaning elements that may provide a better grasp of the history of a given period. As we learn more about the methods used to produce manuscripts during various periods, our attempts to determine the date and geographic origin of a copy containing no written evidence of either will steadily improve in accuracy. It is readily apparent, however, that the service which codicology can render to all whose work is based on manuscripts depends above all on painstakingly gathering accurate data and meticulously analysing its implications. It is to be hoped that this development will be significantly advanced by progress in cataloguing,[23] and more particularly in describing manuscripts. This handbook itself is indebted to the remarkable work done in the past twenty-five years by the authors of modern catalogues, to whom an acknowledgement and thanks are due.

These modest yet indispensable tasks entail the use of terminology as precise as possible. Thanks to Denis Muzerelle, French codicologists have at their disposal a taxonomy that has been drawn on extensively in arriving at the technical terms employed here[24]. It is hard to overstate the need for terminological accuracy, even when naming the basic parts of a codex. When a manuscript written in Arabic script is laid down flat, the spine will be to the right when the reader begins to read; it is also called the ‘back’, and is where the stitches holding the quires are found. The three other sides are ‘edges’: opposite the back, on the left, is the ‘fore-edge’; the top edge, furthest from the reader, is known as the ‘head’, and the nearer edge is called the ‘tail’.

Methodology...

...

*The remainder of this article is exclusively available in the printed version of the related book. The book is available in both electronic and printed formats within Our Publications in the following link:

http://doi.org/10.56656/100099

[1] The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary dates the term to the mid-twentieth century; for the history of its French counterpart, codicologie, see Lemaire, Introduction, p. 1 (notes 1 and 2).

[2] There exists an extensive literature on the history of the manuscript book, especially for the period covering the emergence of the codex. See, for example, C.H. Roberts and T.C. Skeat, The Birth of the Codex; A. Blanchard (ed.), Les débuts du codex ]Bibliologia 9] (Turnhout, 1989).

[3] They have continued, however, to be employed for almanacs until recent times, and for talismans down to the present day. In addition, the epistle of ‘Abd al-Masīḥ ibn Isḥāq al-Kindī claims that the early Muslims left the text of the Qur’ān in the form of leaves and rolls like the scrolls of the Jews, until the Caliph ‘Uthmān changed this practice. See P. Casanova, Mohammed et la fin du monde: étude critique sur l’islam primitif (Paris, 1911), p. 121; G. Troupeau, ‘al-Kindī’, El2-V, pp. 123-124.

[4] In referring to the Torah, the Qur’ān employs the specific term Tawra (Qur’ān III: 3, 48, 50, 65, 93; V: 43, 44, 46, 66, 68, 110; VII: 157; IX: 111; XLVIII: 29; LXI:6; LXII: 5), which implies that it was known to the Prophet’s listeners.

[5] S. Ory, ‘Un nouveau type de muṣḥaf: inventaire des corans en rouleaux de provenance damascaine, conservés à Istanbul’, REI 33 (1965), pp. 87-149.

[6] Grateful acknowledgement is due to J.J. Witkam for drawing our attention to this manuscript.

[7] For illustrations, see CHICAGO 1981, pp. 219-221, n0 94, colour plate O (Chicago, Or. Inst. A12100, late eighteenth century CE) and U. Derman, ‘Hat’, Sabancı Koleksiyonu, p. 49. Manuscripts in accordion form are common in certain regions of Southeast Asia.

[8] See the chapter ‘The Quires of a Codex’; also MUNICH 1982, p. 140 and fig. 24 (MS. Munich BSB Cod. arab. 2641, dating from the nineteenth century CE).

[9] Hence there is no ‘fold’, as normally there would be: see below.

[10] This is in fact part of a manuscript now dispersed between various collections. For the Paris leaves, see E. Tisserant, Specimina codicum orientalium, p. xxxii, pl. 42; R. Blachère, Introduction au Coran, 2nd ed. (Paris, 1959), pp. 96, 99, 100; G. Bergsträsser and O. Pretzl, ‘Die Geschichte des Korantexts’, GdQ, III (Leipzig, 1938), p. 254; Déroche, Cat. I/1, pp. 75-77. Other leaves are held in other collections: Cairo, Dār al-Kutub (see Moritz, Ar. Pal., pl. 1-12; A. N. Shebunin, ‘Kuficheskii Koran Khedivskoi Biblioteki v Kaire’, Zapiski Vostochnago Otdeleniia Imperatorskago Russkago Arkheologicheskago Obshchestυa 14 (1902), pp. 120-125) and Gotha, Forschungsbibliothek MS. Orient. A. 462 (see J. H. Möller, Paläographische Beiträge aus den herzoglichen Sammlungen in Gotha ]Erfurt, 1844], I, pl. XIV; H. C. von Bothmer, GoTHA 1997, pp. 105-107).

[11] For a discussion of ‘flesh side’, see chapter ‘Writing surface: Papyrus and parchment’.

[12] Other manuscripts may perhaps also belong to this group, in addition to MSS. Istanbul TIEM 51 and 52 and Paris BNF arabe 324 (see note 10 for bibliography): a Qur’ān in the Sayyidnā Husayn mosque in Cairo and the so-called ‘Qur’ān of ‘Uthmān’ preserved in Tashkent. It is difficult to tell from photographs whether the same arrangement was used in the Sayyidnā Husayn manuscript (which allegedly measures 60 x 70 cm, according to F. Neema, ‘Restaurado, el Corán más antiguo’, Excelsior, Sunday supplement [Mexico City, 25 July 1993]); cf. Ṣ. al-Munajjid, Dirāsāt fi ta’rīkh al-khaṭṭ al-‘Arabī mundh bidāyatih ilā nihāyat al-‘asr al-Umawī, pp. 53-54). For the Tashkent manuscript, see A. N. Shebunin, ‘Kuficheskii Koran Imperatorskoi Sankt-Petersburgskoi Publichnoi Biblioteki’, Zapiski Vostochnago Otdeleniia Imperatorskago Russkago Arkheologicheskago Obshchestυa, 6 (1891), pp. 75-81; Ṣ. al-Munajjid, op. cit., pp. 50-52; E. Rezvan, ‘The Qur’ān and its World: VI. Emergence of the Canon: the struggle for uniformity’, Manuscripta Orientalia, 4/2 (1998), p. 47, note 11 (bibliography of publications in Russian); compare the folios sold at Christie’s in London on 20 and 22 October 1993 (lots 225 and 225 A) and on 19 and 21 October 1993 (lots 29 and 30). The dimensions of these manuscripts seem to indicate parchment made from the skin of a goat, according to the figures given by Reed (Ancient skins, parchments and leathers, p. 130).

[13] That is, stitched through the entire thickness of a gathering along the inner margin, a short distance from the edge; see Muzerelle, Vocabulaire, p. 179.

[14] U. Dreibholz, ‘Der Fund von Sanaa: frühislamische Handschriften auf Pergament, in P. Rück (ed.), Pergament: Geschichte - Struktur - Restaurierung - Herstellung (Sigmmaringen, 1991), p. 301, note 9.

[15] D. James, After Timur: Qur’ans of the 15th and 16th centuries (London, 1992), pp. 18-23.

[16] See the next chapter, ‘The Writing surface: Paper’.

[17] Although somewhat dated, the proceedings of the symposium on Les techniques de laboratiore dans l’étude des manuscrits (Paris, 1974) offer a glimpse of the possibilities offered by such techniques. As regards identification of the composition of inks, pigments and dyes, a brief discussion of recent methods will be found later in this introduction; see also the chapter on ‘Instruments and preparations used in book production’. Finally, it is worth citing the long experience in this area acquired by the Istituto Centrale per la Patologia del Libro in Rome

[18] J. Berque, ‘The Koranic text: from revelation to compilation’, in G. Atiyeh (ed.), The Book in the Islamic World (New York, 1995), p. 25.

[19] F. Déroche, ‘The Ottoman roots of a Tunisian calligrapher’s tour de force’, in Z. Yasa Yaman (ed.), Sanatta etkileşim = Interactions in art (Ankara, 2000), pp. 106-109.

[20] KuWaIt 1985.

[21] Aspects of the issue of the respective roles of the two disciplines are discussed in Lemaire, Introduction, p. 3, notes 4 and 6

[22] Sellheim, Materialen 1 and 2. The term used by German specialists, Handschriftenkunde, is older and has a broader meaning than codicologie in French, which may explain this different tendency. In France, a similar standpoint was adopted with the founding of the Institut de Recherches et d’Histoire des Textes, where codicological studies place great emphasis on the history of texts.

[23] See the concluding chapter on ‘Codicology and the history of collections’.

[24] Denis Muzerelle, Vocabulaire codicologique: répertoire méthodique des termes français relatifs aux manuscrits ]Rubricæ, 1] (Paris, 1985).

| Source note: This article was published in the following book: Islamic Codicology: An Introduction to the Study of Manuscripts in Arabic Script_ English version, 2005, Al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation, London, UK, pp. 11-23. |