Abid Reza Bedar

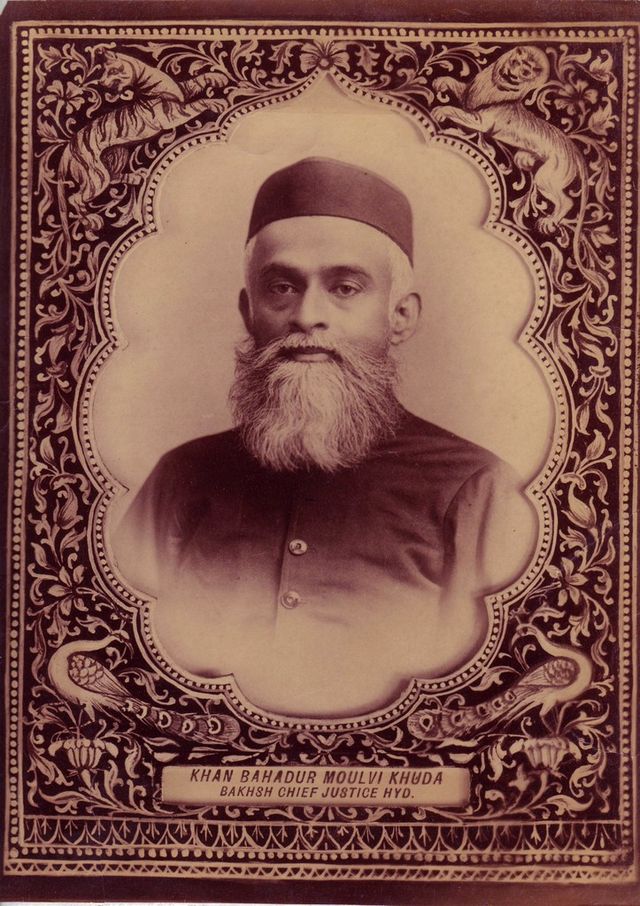

The organisers of this conference, Al-Furqān Foundation, whom I thank at the outset for inviting me to participate in their conference, have asked me to present a report on the state of preservation of Islamic manuscripts and the on-going related activities of the Khuda Bakhsh Oriental Public Library (KBL). Also, as the sole Indian participant, I should like to present an overview regarding the maintenance and preservation of manuscripts found elsewhere in India.

KBL, housing about 18,000 Arabic and Persian (Islamic) manuscripts, only a few of them illustrated, is located in Patna, the Patlipatre of the Great Ashok and the Azimabad of the progeny of the Great Awraugzeb. A thousand kilometres east of Delhi, and near Calcutta to the east and Kathmandu to the north, Patna is situated on the banks of the mighty River Ganges (Gangs). Quick flows the Ganges for most of the year, but it becomes furious during the 3 months of the rainy season and plays havoc. The river flows hardly 200 metres from the library, but it has never been unfriendly to the institution, and, topographically speaking, will not be so in the foreseeable future.

The proximity of the Ganges does, however, affect the library in some other ways. Positively, it cools down the summer. Negatively, it increases the humidity in the winter and during the rains. However, both heat and humidity are being taken care of the former through air-conditioning, and the latter through electrical and chemical devices, and also through manual caretaking.

In the past decade, KBL has been exposed to the problem of air pollution. When KBL was founded in 1891, it was nearly as close to a busy road as it is today. However, the road expanded by four metres and the space belonging to the library shrank proportionally. Now, the distance between the library and the road is ten metres. The roadside location is advantageous for an institution in many ways. Perhaps it might have been so for KBL in the past, but today certain recent developments make this road the busiest passage for automobiles, used by 90 per cent of all traffic.

This diesel/petrol pollution combined with the noise pollution created by religious and political processions, half of which use this road, have turned the erstwhile ideal location of the library into a most unfortunate one. We have contained the potential harm to a large extent by raising the height of the boundary wall four times and by growing trees (cesurine and ashok) as high as the library building itself. However, these measures may not prove satisfactory in the near future and therefore we are thinking of moving the manuscript part of the library to a safer place near Government House.

As for the technical part of the report, I should perhaps note that the normal preservation activities KBL has been adopting represent very little that is not known to others or not adopted at other places. However, if this somewhat lengthy description is in the least beneficial to anyone, it is worth recording. Yet it would not be fair to consume the time of the learned participants of this conference by giving full length details regarding standard preservation measures. Hence, I present a short, informal outline which may be elaborated on if called for.

- The building is damp-proof, air-conditioned, with all provision necessary in the interest of preservation. The ground floor is preferred for storage of manuscripts.

- The wooded surroundings of the building counter the hot, dry, and dusty conditions.

- Chemical spraying inside the building checks the growth of pests.

- Dusting and cleaning manually and with a vacuum cleaner.

- Fire-fighting and fire extinguishing arrangements.

- Repairing, laminating, and binding under careful supervision in the bindery inside the library.

- Fumigation of almirah type as well as a big chamber.

- A preservation laboratory looking after the essential prerequisite steps before the manuscript is properly bound: ink test, de-acidification, application of pesticides wherever necessary, etc.

- Caretakers watch for infestation inside the building or within the collections themselves. The preservation chemist is alerted whenever necessary.

- Microfilming is underway to avoid frequent direct handling of a manuscript, and to have a replica, in the event of some incident, one set remains in the library, the other at a sister institution under heavy care.

- Automation: efforts are on to bring the entire collection on computer record.

- Manuscript over-crowding is being dealt with by keeping the material of peripheral importance in an inspection sequence, that may lead to a process of weeding-out whenever necessary.

These and quite a few other normal practices are currently followed at KBL and on this account there is little that KBL may offer of special experience.

However, we do have some new information to convey to the conference regarding the potential danger to the very survival of Islamic manuscripts throughout India. Other manuscripts are lingering on, unused, dishonoured and unsung in some 500 private collections of which eight are located right in or around Patna (Phulwari, Maner, Bihar Sharuf, Islampur, Sulaimia Sunni, Sulaimia Shi'i, Imadia, and Munamia). Most belong to khanqahs (monasteries), whose custodians are not ready to part with the manuscript holdings. At least one of these collections was found almost destroyed and others with pages stuck to each other well before KBL came to save them on the spot. Such interventions fall short of providing these institutions their minimum requirements. But something is better than nothing. And that something becomes more significant when we add that KBL is also preparing handlists of these collections and making microfilms of the most rare items to preserve at KBL itself. Thus, there is the need to educate other smaller institutions to share the sacred mission so that the experiment made at KBL on a limited scale may be expanded to cover the entire country.

The unfortunate state of private collections is understandable (grand exceptions: Muzammil Library, Aligarh, founded by Nb. Rahmatullah Khan, and Abul Khair Library, Delhi, founded by Hzt. Zaid Abul Hasan Faruqi, both of which have been handlisted by KBL). But it is difficult to understand that the major part of the Tonk collection has lain buried in the National Museum of India since 1951, when it was carried there on loan by special request of Abul Kalam Azad. A proper catalogue has not yet been published, nor even a handlist of the collection. Moreover there is no adequet record of the valuable collection of the museum itself. Rampur Raza Library is one of the finest collections of Islamic manuscripts in the Indian sub-continent. Its Arabic catalogue is still incomplete after the sad demise of S. A. Arshi, the late librarian, and its Persian catalogue is not yet compiled. At least a handlist for its Persian manuscripts has been published by KBL. Similarly, the collection of the Aligarh Muslim University, of which some old listings are available besides a few catalogues stored with the collection, is yet to be handlisted and catalogued. At least a complete inventory of Urdu manuscripts held at the university has been brought out by KBL.

Slowly but surely I am bringing home a non-conformist view of preservation. Preservation, in itself, is one thing. But knowledge preserved is knowledge contaminated, or buried, if it is not spread over to scholars. Dissemination of knowledge is therefore an important dimension of preservation. This is done through cataloguing, handlisting, and facsimile editions. After all, the world famous collections of the Umayyads and Abbasids are preserved only in Ibn Nadim's al-fihrist. Nazeeria Library of Old Delhi is partly gone with the wind and partly acquired by Hamdard but is preserved in the references of its 3-volume handlist. Saeediya Library at Hyderabad was burned during the recent riots leaving the memories of its existence in a handlist only.

This brings us to yet another dimension: fire as the preferred tool of the extremist. God forbid, it may be the Khuda Bakhsh next time. While in Hyderabad it was Hindu fanaticism, it may be Muslim fanaticism in the case of Khuda Bakhsh, as was being planned once in 1989 (on the occasion of Khuda Bakhsh’s South Asian Seminar on Qur͗āns), and again in 1992, when the director of the library held, in his personal capacity, that Hindus were not kafir. In 1967, however, the then chairman of the library Governor Iyenzer, whispered to the director, Iqbal Husain, that one match stick would suffice for the entire library. This time the reference was toward Hindus' fanaticism. The issue in question is satanic religions versus God's religiousness, and where we stand.

We have to educate both Hindu and Muslim fanatics in the human loss, the loss of preserving the human heritage, the loss of love which is destined to defeat the loss of hatred as our experiments in the Khuda Bakhsh demonstrate. We hope the Hindu youth in his twenties or thirties will begin to approve the humanist values of Islam. The experiment needs duplication elsewhere if we are to preserve our heritage in the India of today, or if we can create the conditions to tame the brute in man. Human beliefs turned brutal may be much more harmful than termites and more devastating than the fire, as I myself witnessed in Patna in 1984, in the weeks after the Indira Gandhi assassination.

Let us try to see life as a whole, life in its entirety. Only then it may dawn upon us that this Rumi's elephant is not the fan-like ears nor the pillar-like legs but an elephant in its entirety. If our heritage is to be preserved it will be preserved technologically; but at the same time it is to be preserved by disseminating the knowledge contained therein, knowledge which transforms the brute into a gentle breed who preserves his heritage for coming generations.

| Source note: This article was published in the following book: The Conservation and Preservation of Islamic Manuscripts, Proceedings of the third conference of Al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation, 18th-19th November 1995 - English version, 1995, Al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation, London, UK, pp. 15-20. Please note that some of the images used in this online version of this article might not be part of the published version of this article within the respective book. |