Ursula Dreibholz

| Article contents: History General Information Parchment Condition Conservation treatment Classification Permanent storage Appendix Bibliography |

History

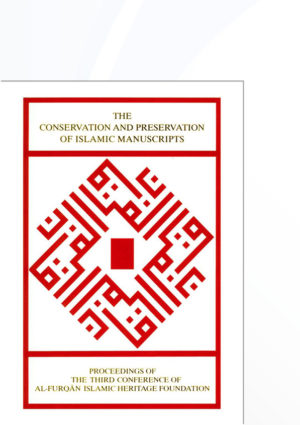

The west wall of the Great Mosque of Sana'a, the capital of Yemen, collapsed under the impact of heavy rains in 1971. Rebuilding of the wall started the following year, and in the process a large number of fragments from very early Qur͗ān manuscripts was brought to light from the space between the ceiling and the roof of the mosque.

Soon the outstanding importance of the find was recognised by the authorities.1As the question of the preservation of the find arose, the government turned down an offer to send all the manuscripts to Denmark for restoration there, but it then accepted a special project, funded by the Cultural Section of the Foreign Ministry of Germany (West Germany at the time), proposing to restore and catalogue the fragments on location in Yemen. This project lasted from the signing of the bilateral agreement in the autumn of 1980 until the end of 1989.2

General Information

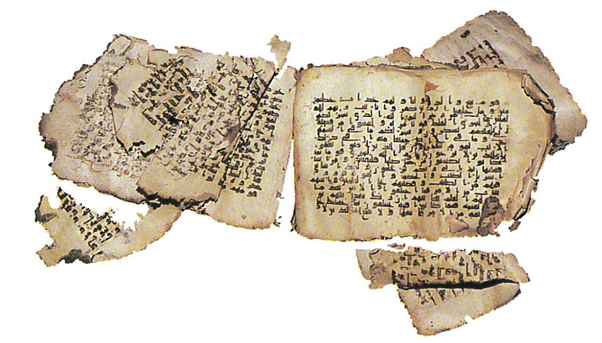

The number of fragments written on parchment has been estimated at 12,000– 15,000. There are also many fragments written on paper, but it is difficult even to approximate their number. Priority was given to the parchment fragments since they are the older and more important ones. There was no time at all to work on the paper fragments during the project, and therefore the following text deals exclusively with the material on parchment.

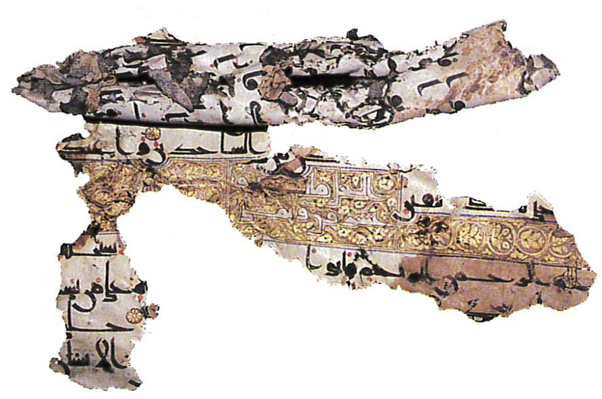

No written dates were found but experts agree that most of the manuscripts are datable to the first three or four centuries after the Hijra, i.e., 7th-10th or 11th centuries AD. The script is mainly Kufic, although there are a number of examples written in the oldest form of the Arabic script — Hijazi.3

Almost all the parchments contain Qur͗anic texts, only less than 150 (that is, approximately one per cent) are non-Qur͗anic. These may be Ḥadīth, religious commentaries, even a few remnants from medical books, and some mostly fragmentary ownership documents. Close to 1,000 different volumes of the Qur͗ān have been distinguished so far. Sometimes a lonely single leaf is all that is left of a volume; on the other hand, in a number of cases a substantial part of the text block is still preserved, but in general just a few leaves represent one book. Not one volume is complete!

All this raises the question why these Qur͗āns came to such a fragmentary and dispersed state, and how they came to be 'hidden' in the roof. The generally accepted view now is that the roof was not a hiding place; if it had been one would expect to find the most valuable and complete volumes there. But books just do not get scattered like this, even under the most unfavorable circumstances. The conclusion is rather that it was a resting place for Qur͗āns, or part of Qur͗āns, that were not used anymore. And what better abode for the Holy Book than in the sacred confines of a mosque?

Parchment

Like leather, parchment is made from animal skin, but by a different process. No tanning agents are used but the skin of freshly slaughtered animals is soaked in lime water for several weeks to loosen the hair. A thorough rinsing is necessary before the skin is stretched onto a frame. During the drying process the flesh side is scraped with a rounded knife in order to remove all adherent pieces of fat and flesh, and considerable pressure is applied while doing so.4 Both sides of the hide are then repeatedly rubbed with chalk and pumice stone for smoothness, although on oriental parchment the difference of hair and flesh sides is left very obvious. There are many cases where the script still perfectly adheres to the hair side, whereas it may have completely crumbled off the somewhat rougher flesh side. In contrast, occidental parchment makers worked hard to give the two sides the same appearance, often so successfully that one cannot easily distinguish the one from the other.

Thickness and size depend on the age and the kind of animal used; smaller and younger animals produced smaller but thinner and more flexible parchments. Therefore, writing parchment always comes from young animals; the skin of older one is already too thick and not suitable. The skin of any animal can be used for parchment making, but the most common ones are goat, sheep, and calf, the same animals that are also used for human consumption. And the material here seems to belong to these same species.

Condition

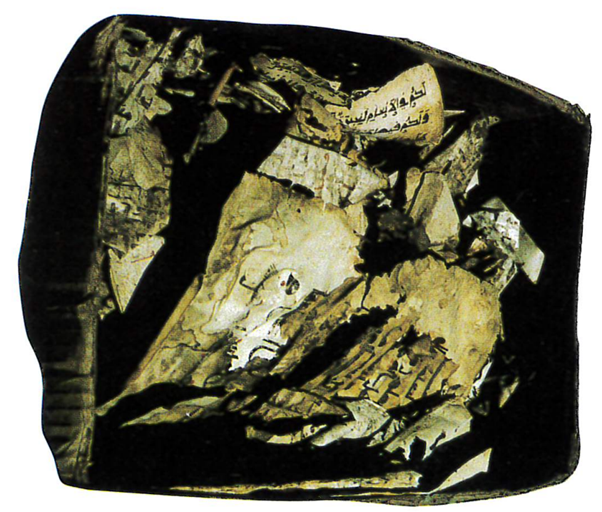

The condition in which the objects were found ranged from very good to almost totally destroyed. The parchments were exposed to water due to the leaking roof and to insects and rodents. But one has to consider as well that many of the manuscripts may have been already considerably damaged before they were deposited in the roof. The ever present dust in Sana'a was also an important factor; together with the water it sometimes caked the leaves together in such a way that virtual bricks were formed. However, the dryness of the climate did not seem to cause any permanent damage.5

All of the manuscripts were at least dusty. Many showed additional dirt, often encrustations, especially where dust and water had mixed. Pages were often stuck together in some cases, the writing was irreparably washed away, or the parchment had rotted beyond the point of possible consolidation. The impression that blackened areas were burned is misleading; these are cases where the parchment has totally disintegrated through prolonged exposure to water or intense moisture. Water was also the cause for some parchments to shrink. Therefore, a great percentage of the damage can be attributed to water. There were occasional heavy accumulations of fly spots (deposits left by flies) and numerous losses caused by insects and rodents, and some obviously by humans. Moreover, most of the leaves were folded, rolled, creased, torn, etc.

Whole pages measure anywhere from4 x 5 to 45 x 50 cm. The ink of the script is mostly of a dark brown or brownish-black colour, a few examples are light-brown, some are almost black. No analysis of the composition of these inks has been made yet, but it seems that a great percentage are iron-gall inks.6

Colour was used not only for the usually red dots of the vocalisation marks and other pronunciation signs, but also in the occasional decorations, such as verse stops and Sūra headings.

Conservation treatment

The aim of the conservation was consolidation of the present state. The fragments were cleaned and flattened. No 'cosmetic' restoration techniques were involved, although tears and broken leaves were mended where necessary, generally with Japanese tissue or paper. Extremely fragile and damaged leaves were put into envelopes made of thin polyester sheets7 which are open on two sides to allow easy retrieval of the fragments, and ultra-sound welded by dots on the other two sides, so air now is assured. In this way even the most vulnerable leaves can be handled and looked at from both sides.

The general method of treatment was very simple, although it did demand concentration, patience and sensitivity, since each individual fragment could respond to the treatment in a slightly different way.

First, all loose dirt was brushed off carefully, and to soften the rigid parchments they were placed in a humidification chamber. The construction of this chamber was very simple; it is clay assembled, cheap, very sturdy, practically indestructible, did not need energy and hardly any maintenance, except for occasional cleaning, and it was quiet:

To assemble the chamber, a shallow tray with water of room temperature is placed into a larger and deeper container. Sheets of nylon netting, the edges reinforced by strips of strong plastic, give support to the fragments. The nets are in turn supported by 'frames' made of styrofoam, allowing enough space between the nets for the placement of the parchments. The uppermost net can be covered with a layer of blotting paper, which could be left dry or moistened slightly, or wetted considerably — an easy way to regulate the moisture content of the air in the chamber, and to delay or speed-up the softening process. Finally, a cover, simply made of a wooden board with a thin layer of foam rubber glued to the underside, very efficiently seals in the humidity.

It was usually sufficient to leave the parchments in the chamber just overnight. Exposure to high humidity for longer periods should definitely be avoided because mould will develop after only 2-3 days!

Consequently, rolled and folded leaves could be unrolled and unfolded easily, and pages stuck together could be separated, sometimes with the help of a scalpel. Dirt was cleaned off with a cotton ball moistened with a solution of water and alcohol (ethanol), at a ratio of one part water to four parts alcohol by volume.8

This solution removes dust and dirt very effectively, and it softens encrustations and fly spots sufficiently so they can be easily scraped off with a scalpel. (It helps to have scalpels of various sharpness at hand!) The solution also does not affect the ink or paint when applied with caution. But rare should be taken that the binding medium in ink or paint has not softened too much in the humidification process.9

Irreversibly decomposed parts, like the gelatinised edges of holes caused by water damage, were cut away — as narrowly as possible. (In general I tried to avoid such drastic measures). The hair side of the parchment was always dampened first because it does not absorb the moisture to the same degree as the more susceptible flesh side. In this way the very annoying curling of the edges of the moist parchment could be at least postponed. It could also be observed that fragments which had been exposed to excessive moisture or directly to water at a previous stage (clearly indicated by greater decomposition, shrinkage, or discoloration) were more hygroscopic (sensitive to the humidity in their environment), even when they had been in a dry state for a long time already.

The trickiest part in the whole operation was to stretch and flatten the fragments sufficiently to remove creases, smooth out curling edges, and stretch shrunken parts. This was accomplished by placing the parchments between two leaves of wax or silicon paper, which ensured that no ink stuck to the paper and no paper fibres stuck to the moist ink. Lifting the upper cover paper partially, a part of the curling edges is flattened, either with fingers or with the help of tweezers. This was usually done only section by section, each flattened area being weighed down immediately in order to free the hands for dealing the next problem area. Each straightened part had to be held down with the wax or silicon paper over which a 'brick' (made of glued-together pieces of board) was slid. That, in turn was weighed down with a small but heavy metal weight. The metal weights should be covered with soft fabric so they can be placed directly onto the parchment if necessary, i.e., when shrunken parts have to be stretched. The 'bricks' are very useful, and since they do not warp they provided an absolutely even surface. Several sizes of these should be prepared.

This procedure may have to be repeated several times, although generally once is enough. But especially when stretching shrunken parchment one has to exercise extreme care and proceed very slowly, otherwise the parchment will tear.

One has to check after about ten minutes, before everything has dried too much, if all the edges are really straightened. Folded-over edges tend to become ugly, thick, shiny, and transparent when pressed.

After approximately two hours the parchments were nearly dry. They were then sprayed lightly with the alcohol-water solution again, placed between larger sheets of wax or silicon paper and boards, and were put into the press under very light pressure, (Moist parchment, when pressed too strongly, becomes irreversibly transparent!) After a day the wax or silicon paper was replaced with blotting paper since there was no further danger to fibres and sticking to each other. The fragments were then left in the press between the blotting papers for four weeks or longer.

Classification

After this treatment the parchments could be handled carefully, and were ready for the next step — determining their textual content. This part of the work, identifying which Sūra and āya (verse) came at the beginning and end of every page or smaller fragment, was done by my Yemeni co-workers, some of whom were involved in the conservation process as well.

The final step was also the first step toward cataloguing the fragments10. First, it was necessary to find out if a particular leaf belonged to one of the 1,000 or so established Qur͗ān volumes, or if it represented a new volume needing a new signature. For this process, it was necessary to rely on a few obvious criteria which could be identified quickly. The first director of the project here in Sana'a11 developed a system in which the lines on a page were counted and their length measured. These two numbers constitute the first two numbers of the signature of a specific volume of the Qur͗ān.

For example "16-20" means that there were 16 lines to the page and the lines not longer than 20cm. Of course, there may be several Qur͗āns with these same criteria, distinguished from each other by different script, format, etc. For each of these, an individual number was added at the end of the signature, i.e. 16-20.1, 16-20.2, etc.

In those cases where the number of lines on a page was inconsistent within a volume, the first number of the signature was always "01". Thus, 01-17.3 designates the third codex with a changing number of lines no longer than 17cm. The range of the number of lines was marked separately; it was thought too confusing and cumbersome to include them in the signature For example: "12, 14-16, 19, 20" shows that there were pages with 12 lines, none with 13, again pages with 14-16, none with 17 or 18, and some with 19 lines.

Where either the number of lines or their length could not be established the appropriate symbol "00" was used. Therefore, 00-15.1 describes a fragment torn horizontally on which the lines could not be counted, but with existing lines not longer than 15cm; finally this is the first example with these particular area.

In contrast, 15-00.4 designates a leaf torn vertically, it is clear that there were 15 lines on the page but whose length cannot be measured, and finally that this is the fourth such case.

Permanent storage

My main concern during the last yeas of the project was the permanent storage of the already restored fragments.12 Safety for the objects, easy handling, and quick information retrieval were my priorities. Also, I had to work with the material we already had here in Sana'a.

A single leaf or a few leaves of a Qur͗ān were stored in flat folders lined with thin acid-free board. About 20-30 of these folders were housed in open-ended plastic boxes of which we had a great number. They facilitate handling considerably but were put on the shelves on their broad sides so the opening is facing forwards. The folders were laid in there horizontally, the attached labels with the signatures could easily be seen, and individual folders could be taken out effortlessly. The fragments were generally too fragile to be stored in a vertical position because the edges could be damaged further with each handling.

When lifting the cover13 of a folder, a sheet of polyester film ('Mylar' or 'Melinex') gives an open view of the object while protecting it at the same time. It is itself held down in turn by the side-flaps of the folder. Even an accidental drop of the folder will not allow the leaves to fall out, but if a closer examination is wanted they can be easily retrieved by just lifting the flaps and the sheet of plastic.

Thicker volumes were stored in drop-open boxes. The parchments were too weak and fragmented to be resewn; moreover, all the volumes were incomplete and there is always the possibility of other leaves emerging from the rest of the unrestored or not yet classified material. The book block with the often very fragile edges is protected by a wrapper of thin acid-free, board with, again, a sheet of clear plastic on top. Because parchment always has the tendency to warp and curl if not held under slight pressure,14 and because it always 'remembers' the original three-dimensional shape of the animal, the fragments, with the wrapper, are placed between two boards, tied together with linen bands. The bands allow the thickness of this assemblage to stay flexible, so additional leaves, when found later, can be inserted. A window is cut out from the upper board which allows the first page of the volume to be seen. Thus, just by opening the box, and without untying the bands every time, one can see the script at a glance and judge if a new fragment fits in.

There is a folder for every signature and the labels are colour-coded: different colours for objects either too big or too bulky to fit into the regular folders. In this way one can tell whether the fragments are to be found in a box or in the cabinet for oversized manuscripts. Also, the labels are placed on the folders in a step-like fashion: each new first number placed a label-length away from the former, i.e. all labels starting with the number 16 would be in the same position, and all labels with the number 15 would be together before, and the ones with the number 17 after those with the number 16. In this way, any error in filing a folder can immediately be recognized.

Folders and boxes were stored horizontally, in the tradition of the Islamic book, in specially made cabinets. The storage and conservation facilities are in the Dār al-Makhṭūṭāt, the Manuscript Library, located in the old city of Sana'a, opposite the Great Mosque, the place where the fragments were originally found.

I am convinced that stored in this manner and barring unforeseen catastrophes, these invaluable Qur͗ān fragments will survive another 1,000 years.

Appendix

A final word of caution: The conservation treatment described above is very well suited for material such as the Sana'a find — separate parchment leaves kept flat and not handled too often. After treatment, the leaves will be dry again and will have limited flexibility. Therefore, the treatment is not appropriate for bound parchment manuscripts!

There are various methods for softening dried out and rigid parchment. But I want to add that my personal conservation philosophy, together with that of the majority of my colleagues, is not to do too much, and to use natural materials wherever possible! Introducing foreign substances to conservation has often proved disastrous in the long run. There is no question that modern techniques and materials can sometimes be of great value, but I recommend great prudence in their use, and would certainly warn against applying them in a general way. Unfortunately, we usually do not know enough about their long-term effects. Invaluable works of art and documents have been destroyed because a new method initially seemed so easy and practical.

In general, please do not use synthetics in treating parchment!

In recent years, the treatment of dry and brittle parchments with urea solution has been promoted. I do not recommend it! It is true that it softens the parchments and renders them flexible, but the ones that were treated in this way before I arrived have lost their characteristic 'parchment' look and feel, and are unpleasantly shiny on the surface and even partially transparent.15

Another method that has gained rather widespread use, and which I do not recommend either, is the immersion of the parchment in polyethylene glycol. Again, it keeps the parchment flexible, but also renders it more hygroscopic16, and it involves the irreversible and permanent introduction of a foreign material into the parchment. Nobody really knows what effect it might have after a few hundred years.

Treating parchment with parchment size is to me the only acceptable method. (Sizing with gelatine is preferred by some, but personally I do not feel as comfortable with it.) One has to take great care with modern parchment when making the size, various chemicals are used in the production of modern parchment17 which could introduce unwanted impurities. Ask the manufacturer! It is also not advisable to use old parchment.

The basic recipe: cover small parchment clippings with distilled or deionised water. The best parts are the greasy and hairy edges of a skin; never use parchment with writing, printing or surface coating. Soak them overnight or longer. Then heat the clippings in the same water for 24 hours (this can be done in batches18) in a double boiler at a steady temperature of 60°C.19 Never let them boil, because this causes the size to lose its strength. Then strain the 'broth' through a cloth. The size is not very durable but it can be frozen (for example, in Ice-cube trays).

It can also be mixed with wine vinegar and alcohol (one part of each to three parts of the broth), which makes it usable at room temperature, helps penetration, and enhances shelf life. Some people think the vinegar too acidic, others claim it will disappear due to the alkaline nature of the parchment; it can also darken some pigments20. The parchment should be lightly sprayed with alcohol (ethanol) before application to help the size penetrate more easily.

Bibliography

This is obviously not a comprehensive bibliography; I just would like to give an impetus for further reading.

A useful compilation of various methods of parchment repair, with an extensive bibliography, was published in 1994 as part of the "Paper Conservation Catalog" by the Book and Paper Group of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, 1717 K Street NW, Suite 301, Washington DC, 20006, USA.

Cains, Anthony, "Repair Treatments for Vellum Manuscripts", The Paper Conservator, 7 k 1982/83) The Institute Paper Conservation, Leigh Lodge, Leigh, Worcestershire, WR6 5LB, UK.

Giuffrida, Barbara, "The Repair of Parchment and Vellum in Manuscript Form", The New Bookbinder, 3 (1983) Designer Bookbinders, 6 Queen Square, London WC1N 3AR, UK.

| Source note: This article was published in the following book: The Conservation and Preservation of Islamic Manuscripts, Proceedings of the third conference of Al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation, 18th-19th November 1995 - English version, 1995, Al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation, London, UK, pp. 131-146. Please note that some of the images used in this online version of this article might not be part of the published version of this article within the respective book. |