Abdallah Yusuf al-Ghunaim

The heritage of Arabic geography forms a vital pillar in Arabic literature and in the heritage of Islamic civilisation. The study of this heritage therefore remains a field that lies wide open to researchers and scholars. Works on Arab geography have been published in the past and continue to be published today. However, there are a great number of considerations which ought to be taken into account when making a proper evaluation of this unique heritage. It is a heritage that has played a large part in the development of geographical thought and the introduction of new approaches and ideas and therefore holds a valued position in the scientific world.

This paper is an attempt from a specialist, who spent approximately 30 years working on this heritage - in research, study and verification - and have come across a number of errors made by others working on this material. I have also seen come to light a number of the links which connect the geographical texts, maps and terminology. These reveal the true benefits to be gained from a serious investigation of the texts in their various editions. In this paper I shall give examples and models which are intended to illustrate the aim which we are hoping to achieve in this paper.

In my view, if the subject of this paper is to be covered in an adequate manner research must be undertaken with five different considerations in mind: the evaluation of the books which were published following work done in the nineteenth century; the review of some of the books completed in the last two decades; the necessity of involving specialised geographers in the assessment of manuscripts and in the analysis and interpretation of terminology; the importance of ensuring that work on the illustrative maps of early Arabic geography is subject to critical study and, finally, the recommendations which follow from these considerations.

Evaluating of the geographical heritage in the research and publication completed in the nineteenth century

A hundred years or more have passed since a significant part of our geographical heritage was investigated and published by writers such as Eddie Rēnaud, de Celan, Wüstenfeld, de Goeje and others. As a consequence most of the studies and books on Arab geography published recently rely heavily on the works of the early great Arabists. Of the collection of works published between 1870 and 1894 by de Goeje in the Biblioteca Geographorum Arabicorum, which includes nine of the founding works on Arab countries - and were only published in the Arab world almost a century after their original publication in Europe - only four have been the subject of critical revision. This is also the case for many books of regional geography, geographical lexicons, travel accounts and books of wonders. An example of this is Taqwīm al-Buldān by Abū Fidāʾ which received a great deal of acclaim with its translation, study and publication in Europe but still to this day no outstanding work of Arabic study on the book has appeared in print. The edition published in Paris in 1840 by Rēnaud and de Celan is still the basic reference work for the book although tens of copies of the manuscript of this valuable book have since been discovered, whose study and investigation could doubtless provide great benefits. There remains a great deal of important study and critical research to be written on this work which would be facilitated by comparative research and examination of the contents of the book in the many different manuscripts available.

The same could be said of al-Bakrī's book, Muʿjam ma Istaʿjam, or Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī's Muʿjam al-Buldān. The former was published by Wüstenfed at Gottingen in Germany between 1870 and 1877. This edition was based on a number of manuscripts to be found in various libraries in Cambridge, London, Leiden and Milan. Between 1945 and 1951 Muṣṭafā al-Saqqā published an Arabic version of this work in four volumes in Cairo, based on Wüstenfed's edition and supplemented by the transcripts he came across in Egyptian libraries. There remains a number of copies of the manuscript of al-Bakrī's book in libraries around the world which were not taken into consideration by either Wüstenfed or al-Saqqā. Among these is the copy which recently came to light in Morocco. Further attention and comparative study of these various manuscripts would give result in a definitive and much improved edition of the gazetteer.

Wüstenfed drew attention to the discrepancies between different manuscripts of the dictionary. He explained this as being due to the fact that after al-Bakrī first wrote the book he distributed it among various people and rulers, after which he would return to the work to make corrections, observations and revisions. Things would occur to him which he had not thought of when he first wrote the book, and he would make corrections in the margins in some copies or, as Wüstenfeld says, on slips of paper which he would paste into the book under the relevant subject heading. Some of the transcribed copies contained these revisions in full, in others the scraps and slips of paper are compiled separately and in yet others they appear incomplete. Therefore was available in circulation different manuscripts.

One of the oldest manuscripts of al-Bakrī's work is the copy which is kept in the al-Azhar library in Cairo (ms ref.262). This is an incomplete copy. The date of its publication is given as 695 hijrī. It is divided into two parts. The first part is lacking the first pages and begins with what corresponds to page 132 in the al-Saqqā edition, and ends with the end of the first part. The second part corresponds to the published edition. This copy is written in a beautiful Andalusī script.

Muṣṭafā al-Saqqā refers to these copies and describes them as being ‘outstanding in terms of condition and accuracy and clarity and, if it had been complete, it would have been superior to all the other original sources available for this book. There in the margins, in the handwriting of the author, is the evidence that it dates back to its very source.’

Although al-Saqqā mentions the notes in the margins of this copy, he unfortunately does not make use of them and indeed does not include the contents of these marginal notes, supplements, additions and corrections in his book. Despite the important annotations compiled from the book, al-Nawaādir by Abū ʿAlī al-Hağrī, with supplements of a less important nature by Abū Ḥātim, Ibn Duraid, Ibn Hishām, Abū al-Faraj al-Iṣbahānī and others.

From the marginal transcriptions copied from Abū ʿAlī al-Hağrí, which comprise more than 80 of the additions found, the majority are connected to new topics being added to the original book. These are written in the original manuscript in their relevant position according to the order of the dictionary. Below are a few examples of these supplementary additions:

- Al-taghālīl: al-Hağrī says, ‘I asked Sulaymān ibn Yazīd al-ʿUmarī about this and he said; “it pertains to the notification of pass that has been traversed". He said: "from the word taghalghal (to penetrate) which comes under the latter ghayn. Ahill of a steep incline. There are a number of taghālīl.” in another spot he wrote, “Taghālīl: a barrier between the flood and the grass bank intended to free the way of the water and these are known as taghālīlāt.”’

- Jarbān: al-Hağrī says, ‘Jarbān is a flow that is moving away with a valley that feeds a stream.’

- Al-ḥulwah: al-Hağrī says, ‘I asked him [i.e. al-Khulṣī] about al-Ḥulwah the well of Muzayyanah belonging to the Banū Ṣakhr of Muzayynah, he said “it is in al-Munṣarif and springs from Ghayqah and is not in Jī. There is a mosque for the Prophet in Ḥulwah and another in Biḍḍah, which is a white (tilʿah) a mile and half south of Rukūbah. Biḍdah is in Jī is between Rukūbah and al-Rūwaythah.”’ Al-Hağrī says that ʿAyn Ḍabʿah is a well-known as al-Biḍḍah.’

There is no need to mention all the supplements. It should have been up to the researcher to place them in their correct position in the gazetteer and not to neglect these omissions, particularly as it is evident that they are supplements made by al-Bakrī himself. Adding what has been learned recently by way of newly discovered copies of al-Bakrī’s gazetteer to what was omitted by Muṣṭafā al-Sāqqā – the valuable material which is to be found in margins of the al-Azhar manuscript – clearly suggests that a new, comprehensive edition of the gazetteer would be timely. It would shed light on many things which are currently obscured.

In the case of Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī’s Muʿjam al-Buldān there exist at present tens of reliable manuscripts which Wüstenfeld was not able to make use, of when he published his dictionary in the nineteenth century. There is no doubt that some of these contain supplementary material and corrections in relation to the numerous editions that have already been published, for example, the one published by Wüstenfeld at Leipzig in 1866, or that published by Amīn al-Khānjī in Cairo in 1323 hijrī, which was later published by Dār Ṣādir in Beirut. Alongside these manuscript copies, tens of books on the Arabic heritage have been published over the last decade on literature, poetry, history, translation and geography. Many of these refer to sources that Yāqūt also relied on and would be helpful to anyone working on an investigation of his book.

Everything points to the need for a new edition of al- Bakrī’s Muʿjam ma Istaʿjam, and Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī’s Muʿjam al-Buldān as soon as possible. There are valuable additions to be found in the edition of the late Mahmūd Muhammad Shakir – one of the most well-known authorities on gazetteers. There are also historical and geographical corrections which have been made by our teacher Shaykh Hamad al-Jasir over the course of more than half a century. These should be taken together with what al-Jasir published in the way of research and commentaries in various scientific journals, above all, in the invaluable al-ʿArab, or in the books he wrote on the geography, history and literature of the Arabian Peninsula. His writings were corroborated by wide-ranging field studies to ascertain the exact locations of places mentioned in the gazetteers and to verify their locations.

Revisions of research work published over the last two decades

Over the last 20 years or so, the market for the material of Arabic heritage has broadened considerably. Unfortunately, the number of researchers who have not mastered the tools and art of editing has also increased. These people have dabbled frivolously in the field, and have done considerable damage to the texts they have studied. They have been aided in this by university teachers who have not lived up to the responsibilities demanded of those who supervise thesis based on editing of early texts. Plagiarism existed, where work is claimed as original by people who really they have no right to do so.

These practices are not of course restricted to the Arab world, but are also to be found in many of the academic treatises researched and written at European universities. Geography has not been immune to the misuses: works have been published which show little evidence of how important accuracy is, when dealing with the names of subject headings and the descriptions of locations. They are deficient in terms of commentary, correction or analysis of earlier works, and have little to distinguish their writers and their level of skill. One such example is a thesis which earned its author a doctorate from the Facultē des lettres et sciences humaines at the Universitē de Paris III Sorbonne Nouveau in the year 1975, under the auspices of Dr. Andre Michel- a well-known and qualified academic of distinction in the area of research and publication of the Arabic geographical heritage and its translations into French. The author of the work was Adrian Van Leeuwen who examined the text of Abū ʿUbaid al-Bakrī’s al-Masālik wa al-Mamālik. His work comprises three volumes which include the text in Arabic and an index of chapters with an introduction in French on the life of the man, the age in which he lived and his sources. Van Leewen published this thesis in its entirety with support from the Tunisian Ministry of Culture in 1992. It was published by the national foundation for translation, research and studies – Bayt al Hikmah – in association with the Arab Institute of Books (al-Dar al-Arabiyah lil-Kitab). Strangely, Van Leewen worked in collaboration with another person (for the publication purpose) in the investigative research and the editing and cataloguing, although, he does not, as a matter of course, publish or indicate in any way the source of the thesis which he presented - a quite unique case for which I find no explanation at all.

Van Leewen perpetrated some quite abominable mistakes in his examination of the text of al-Bakrī’s book. First he does not refer back to the three extant manuscript copies of the book: not to the manuscript in the Muhammad al-Manuni Library in Rabat, whose history can be traced back to the sixth century hijrī and is one of the most trusted and the oldest documented copy, nor to the copy in the main archives in Rabat (ref. 787 dāl), nor to the copy in al-Nāṣirīyah Library in Kahnu in India, (ref. 59). Secondly, the names of the subject matters are transcribed incorrectly without comment, nor with any indication of any difficulties he has encountered in the text. This is the least we would expect a researcher to do regarding to the editing of a particular text. Van Leewen settled simply for mentioning a deviation in the copy without further enquiry.

To go a little further into our examination of this example, we shall look at the section of al-Bakrī’s book dealing with the route from Basra to Makkah which appears on page 381 of the first part of the book al-Masālik wa al-Mamālik of the Tunisian copy. The relevant phrases extracted from the book are marked in brackets and these are followed by my comments:

(From Basro to al-Siḥābīyah – eight miles)

It should be al-Manjashānīyah rather than al-Siḥābīyah. Yāqūt writes (vol. IV. p. 658), ‘This is a way station which

indicates the route for those who leave Basra seeking Makkah. In the book of Basra by al-Tājī, al-Manjashānīyah marked the boundary beyond the periphery of Basra between the Arabs abd the non-Arabs outside the town.’ See also in the book, al-Masālik wa al-Mamālik of Ibn Khurdādhdhbih (p. 146) and the valuable notes for Ibn Rustah (p.180) and the book al-Manāsik al-Mansūb by al-Ḥarbī (p.575).

(To al-Ḥafīrah – ten miles)

The correct spelling is al-Ḥafīr. This spelling appears in one of the manuscripts which the investigator does not refer to. Yāqūt writes (vol. II, p. 397), ‘al-Ḥafīr is also a way station for the traveller from Basra which marks the pilgrimage route from Basra. Between it and al-Manjashānīyah there are 30 miles. Al-Ḥafṣī writes: if you leave Basra for Makkah you follow the bottom of a cleft and the first water you find is at al-Ḥafīr’. It is noted that Yāqūt estimated there to be four miles from Basra to al-Ḥafīr. This is an obvious error as it is perhaps closer to four farsakh which would make it more like 16 miles between the two places. This is similar to the estimate given by Ibn Rustah and al-Maqdisī which is 18 miles.

(To al-Ruḥail it is 28 miles, to Sanjak it is 26 miles)

Sanjak is given as al-Shajjī by Yāqūt, Ibn Khurdādhdhbih, Ibn Rustah and others.

(To al-Rūhā 33 miles)

The correct name is al-Khārga which Yāqūt tells us is a watering place dug by Jaʿfar ibn Sulaymān close to al-Shajī between Basra and Ḥafr Abū Mūsā on the pilgrimage road.

(To Ḥafr Abū Mūsā 26 miles, to Māwīya 32 miles)

Appears in this form in one of the manuscripts of the Masālik. It is one of the places on the road which lies 29 miles from Māwīyah. The investigator does not mention this.

(To al-Sirʿah 23 miles)

The correct name is al-Yansūʿah which is a well-known place on the Basra pilgrim route.

(To al-Simīyah 29 miles)

Al-Samīnah is the correct name, a watering stop belonging to the Banū al-Hajīm with a well of sweet water and a well of brackish water. Yāqūt (vol. II, p. 153) records it as a place before al-Nabāj.

(To al-Sājj 23 miles)

Al-Nabāj is the correct spelling, a well-known place on the Basra pilgrimmage road.

(To al-ʿAwsajah, 27 miles, to al-Qaryatayn 22 miles)

Van Leewen’s edition omits four places which are mentioned in one of the manuscript sources of the al-Masālik as they appear in the gazetteers of Arabic geography which describe the road from Basra to Makkah: Rāmah, Wamrrah, Ṭakhfah and Ḍariyah.

(To Ḥuwaylah 32 miles)

The correct name is Jadīlah as recorded by Ibn Khurdādhdhbih (p.146) and Yāqūt (vol. II, p.43).

(To Malḥah 35 miles)

Falajah is the right name, as recorded by Ibn Khudādhdhbih (p.146) and Yāqūt (vol. III, p.911).

(To Wajrah 40 miles, to Awṭās 24 miles, to al-Sikkah, and from al-Sikkah)

According to the source gazetteer the spelling should be Marrānish.

From this, it is clear that out of the 24 places mentioned on the road from Basra to Makkah the researcher neglects to mention any errors and incorrect transcriptions in 11 of them. He also makes no reference to the four places that were dropped from his text which appear in at least one of the source manuscripts, not to mention other sources. If the researcher took the trouble to glance over any edition of al-Masālik wa al-Mamālik, which is commonplace and readily available, he could not fail to observe the integrity of the text.

If this is the situation regarding only ten lines or so of just one book, what kind of confidence can we possibly have in the rest of the material? And where do we find to examine the work of such researchers simply to point out their flaws and the damage they have done to the texts of the Arabic heritage?

It is truly unfortunate that similar mistakes appear in a new edition of the book, Nuzhat al-Mushtāq fī Ikhtirāq al-Āfāq by al-Idrīsī which was produced by the Italian Institute of the Near and Far East in Rome. It published the works of a number of scientists from different parts of the world between 1970 and 1984, and these works were translated and reprinted in Arabic in Beirut in 1989.

On page 160 of the Rome edition there is a mention of the route from Yamāmah to Makkah. This is a route which meets the road from Basra to Makkah mentioned above at a place called al-Qaryatayn before it continues on to Makkah. A number of mistakes in the names of places found on this section of the road appear in this edition:

Taqjah’s correct name is Ṭakhfah; arbah should be Ḍarīyah; Quljah should be Fuljah and al-Raqībah should be al-Dathīnah.

The involvement of specialised geographers in the study and verification of Arabic geographical texts

Most of the books of Arabic geography which have been published to date, either in Europe or in Arab countries, were researched and investigated by academics who were not geographers by training, but linguists, historians and so forth, and they made an easy line for the actual geographers. They devoted all their efforts to investingate and collate texts. Some researchers fell into common pitfalls, either in the interpretation of the texts or in the commentary on them. Two examples of this are given below.

- In the edition of Faḍāʾil Miṣr by ʿUmar ibn Muḥammad ubn Yūsuf al-Kindī published by Ibrāhīm Aḥmad al-ʿAdawī and ʿAlī Muḥammad ʿUmar (Cairo 1971), in a passage on page 60 the editors interpret the word qaḍab as ‘a term for all trees whose branches rise and spread out’. The word was actually incorrectly transcribed and should have been read qaṣab, which is a harmful plant causing obstructions in canals and ditches.

- In the journey of Aḥmad ibn Faḍlān a tree is mentioned in the land of the Slavs, which is described as follows: ‘excessive in height and its trunk is devoid of leaves. Its crown is similar to that of a palm tree with fine fronds. People come to these trees and cut the trunk at a particular point, below which they place a receptacle into which flows a fluid, more pleasant than Honey, which causes inebriation similar to alcohol in most people.’

The researcher, Dr Sāmī al-Dahhān, an eminent scholar, wonders in the course of his investigation if ‘perhaps it was sugar cane which Ibn Faḍlān was describing’. This is a mistake by the researcher. Sugar cane – as is well known – does not grow in the colder climes through which Ibn Faḍlān passed. Also, the characteristics of the tree as described by him differ from those of sugar cane which does not release a liquid when it is cut but rather needs to be crushed quite firmly to extract any liquid (Risālat ibn Faḍlān, researched by Sāmī al-Dahhān, Damascus 1959, p. 129).

Specialist geographers can provide methods for the examination of any given text which can help in its analysis and authentication. These methods include field studies which help to provide knowledge of the distances to or from a given city or region, as mentioned by the author; research into a particular geographical location which can reveal its connections with earlier civilisations; and analysis of the links between a route and the topography of the area through which it passes. The end products of all these methods are detailed maps which can impact on the text under investigation and help to clarify it.

In my opinion, it is obvious that using such methods can help investigators who are not academically qualified in geography to improve the books they write and, indeed, to carry out more effective research on the early geographical texts. Our master Shaykh Hamad al-Jasir exemplifies this: he supplemented his field studies with a rich comprehensive cultural knowledge which helped him to investigate manuscripts. He connected his work by using maps as indispensable tools of research and elucidation. His research methodology put Shaykh Ḥamad in the vanguard of geographical studies.

Another case is provided by the Englishman, G. Le Strange who could not possibly have attained the results he did in his book, The Lands of the Eastern Caliphate, if he had not applied the methods of geographical research. The same can be said of the great work written by the Russian historian V.V. Bartold, The History of Turkestan from the Dawn of the Islamic Age to the Moghul Invasion. Both these books rely on the early Arabic sources in a very fundamental way, and they provide a brilliant picture of the historical geography of the eastern Islamic World, being based on field research and the analysis of drawings and geographical maps.

I shall now add to the above two subjects a further section about the influence of competent geography on the study of early geographical manuscripts. I shall also look at the benefits which can be gained as a result of a partnership between terminology and information which can be extracted through an informed study of early geographical maps.

Early geographical texts and difficulties of terminology

There is another benefit to be derived from the application of competent geographical methods to the examination and analysis of geographical manuscripts: the ability to investigate geographical terms used in the early books and apply them to works of contemporary studies. Anyone who enters into research or translation nowadays is bound to face the problem of finding an equivalent Arabic expression for a foreign term. This is not always simply a linguistic matter. It is also a problem created in part by Arabic researchers who cut off themselves from the terminology used in the rich heritage of the past. They started transcribing foreign names literally or, alternately, they translated the meaning of a term into more than one word, disregarding the abundance of terms which already existed in early geographical sources in the various fields of physical geography, landscape, human geography and so on. There follow a few examples to illustrate different cases.

The Literal Copying of Terminologies

The Arabic Language Academy in Cairo permits this usage only in cases where it is absolutely necessary, namely where it is impossible to find an existing alternative word or expression in the Arabic language which accurately conveys the precise meaning of the original term (Muhammad Souisi, p. 13). Nevertheless, both geography and geology lexicographers have added tens of foreign words such as cuesta, caldera, delta and karst to the language. These words, along with a number of others like them which have appeared in books written and translated by Arab geographers, have been scrutinised by the Arabic Language Academy which has admitted only those which they deemed necessary. Often, however, these terms were not submitted to rigorous study, either in the field or office, nor were consultations made with Arabic speech patterns to be sure that no alternative word existed which provided the required meaning. One of the examples given above, the term cuesta, would probably not have become familiar in the books of contemporary Arabic geographers if the establishment of this foreign word had been founded on proper scientific field study. This geographic phenomenon (cuesta) was adopted directly without looking within the Arabian Peninsula at the layered speech habits which are associated with the collective mass of Arab tribes. The people of that region do in fact use the word jālāt, or jāl in the singular, and stretches in the shaped pivot. There are believed to be around eight jālāt. These comprise a series of rugged bluffs facing west which rise up steeply on one side and descend gently to the east in accordance with the general inclination of the topography of the Arabian Peninsula. The largest of these jālāt are elevations or rings of hills called Arḍ or altwik mountain which extend overall from north to south for a total of around 800 kilometres and rise to a height of 1,000 metres above sea level. In Kuwait there are also a number of jālāt, the most significant of which is jāl al-Layyāḥ which is a range of hills that extends across the north of Kuwait and which shows the particular characteristic which is now known as cuesta, namely cliffs or bluffs which drop very sharply on one side while sloping gently downwards on the other.

The term jāl, which has been used by the inhabitants of the region for hundreds of years, is a resonant expression in simple Arabic, in both spoken and written forms, and is derived from the very foundations of the Arabic language. The Arabs used the term jāl to describe the wall of a well, the side of a wadi, or the bank of a sea in the sense of signifying the edge or border of something, which is how the use of this term emerged among the inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula. The most important aspect of the term cuesta is therefore that of its having one rugged side which appears as an edge. The term jāl emerged to spread its influence among other lexicographers.

The example which we have just touched upon leads us to another issue of great importance: The term jāl is not found in the early books by Arab geographers, but it is to be found in books on the Arabic language. We are convinced that the Arabic heritage is a closely bonded heritage, yet we find an important element of geography that appears in books on language, history or botany but does not occur in books about geography. One of the conclusions which can be drawn from this is that it is part of the researcher’s responsibility to be equipped with links to facilitate communication and understanding between different parts of the Arabic heritage. This is the way we were taught by our teachers and shaykhs.

Interpretation of a term that comprises several words

The translation of the term ‘water divide’, or ‘water parting’ appears in Arabic in the geographical dictionary of the Arabic Language Academy in Cairo as maqsam al-miyāh and is described as ‘a high point of elevation from which the water descends on two different sides’ (al-Sayad, p. 97). The same term was translated into a composite of three words by Yūsuf Tūnī in the Dictionary of Geographical Terms or Muʿjam al-Muṣṭalahāt as khaṭṭ taqsīm al-miyāh. His description is as follows, ‘an illusory line which runs from a high point over the ground, which divides the course of the tributary streams or separate basins of the river’. (Tūnī, p. 210).

The language dictionaries are devoid of Arabic equivalent for this term, but I have found one equivalent under the subject heading of rifts (silaʿ) in Muʿjam al-Bildān by Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī who writes, ‘Abū Ziyād writes: “Rifts are ways in the mountains, and these enable people to climb up into the passes. They are to be found between two mountains that reach up to the highest point in the valley after which they trace their way through the mountain until they emerge on the brink of another valley. This line divides between the mountains as it goes and then descends into the other valley and emerges from the mountain as in a slope towards open ground. The rift is the extreme point which verges on the two valleys.”’ (Yāqūt, vol. III, p. 117).

This description, as quoted by Yāqūt from Abū Ziyād al-Kalābī, is far richer in its description, explanation and elucidation of what is meant by the term, far better than ‘water divide’ or ‘the line dividing the water’. The description also contains another term which was used in the Arabic translation of more than one word. The word masnad (for example, support, tradition, trace), with its different linguistic variations, is the same term as the English word ‘upstream’ for which the equivalent given in contemporary books of Arabic geography and in the Dictionary of Geographical Terms is ‘the river’s high point of elevation’. (Tūnī, p. 474).

Confirming a term through field work

To a large extent, field studies are considered to be important for choosing among geographical terms. The physical confirmation of an expression can, however, provide great benefits in that it firmly identifies a given term in cases where there are alternative synonyms for the term. In this way field studies can help to correct some of the errors that are to be found in geography books that were written solely on the basis of studying documents. By way of an example it is worth mentioning ʿUmar al-Ḥakīm who writes in his book Tamhīd fī ʿIlm al-Jugrāfīyā (p. 305): ‘The deepening of pits or holes resulting from dissolution in the calcitic rock causes further expansion which grows with the passing of time until the edges between adjacent holes are eaten away. The result of this, is a very large hole which can be several kilometres wide. These are called darāh in the Arab lands and būlīyah in Yugoslavia, and so on.’

From what Dr Ḥakīm writes, it is clear that he considered that darāh were produced as a result of the dissolution by water which occurs within areas of calcareous rock, and the description in the Dictionary reflects this conviction. The word darāh appears described in the Arabic language as ‘wide pits which are to be encompassed by mountains’ (Ibn Mandhūr, vol. V, p. 382). Dr al-Ḥakīm based everything he wrote in terms of explanatory notes for these holes and the subsequent drains in calcareous regions, on this description.

By referring to studies in the field, it becomes clear that the term dārah contradicts what is mentioned above. In fact this phenomenon does not occur in areas of calcareous rock, but it is widespread in the regions inhabited by Arab tribes in the Arabian Peninsula. In fact, Arab geographers have confirmed its description and distribution throughout the Arabian Peninsula. Al-Aṣmaʿī actually wrote a treatise on dārah; and al-Bakrī mentions 22 dārah; Yāqūt al-Ḥamawī mentions 68.

The term was considered to be of special importance for poets and the authors of linguistic dictionaries who broke up these descriptions and extracted what was important from them; later writers competed with their predecessors over the number of dāʾrah they had found.

There is another Arabic term which tallies with Dr ʿUmar al-Ḥakīm’s descriptive outline and that is the word daḥl. These are holes and caves which do occur in regions of calcareous rock and which deepen as a result of dissolution by the action of water. This is a term which appears in language dictionaries and books of Arab geography.

Al-Azharī writes, ‘In al-Khalṣāʾ and around al-Dahnāʾ I saw many (daḥlānā) openings in the rock (daḥlān) and I entered more than one of these. These are features (that is to say holes) created by Allāh beneath the ground. They extend into the earth for a distance of one or two qāmah or more than this. After this there is a bend to the right or to the left. Sometimes it narrows and sometimes it widens in a smooth surface which the pickaxe cannot penetrate due to its hardness. Upon entering one such daḥl I found water. Within that hole, there was water although I could not ascertain its width nor depth nor volume it due to the darkness below the earth. My companions and I drank from the water because it is water from the heavens which comes to it from above and is collected inside it.’ (Tahdhīb al-Lugha, vol. IV, p. 419)

Al-Hamadānī mentions the names of a number of these daḥlān in the region of al-Ṣamādin and remarks that they were a source of water there. these are deep fissures torn in the surface of the earth in which water acuumulates (Ṣifat Jazīrat al-ʿArab, p. 281).

It is very unfortunate that the kind of inaccuracies mentioned here, have found their way into books circulated between teachers and students, as this leads to their perpetuation and dissemination. We should mention that Yūsuf Tūnī copied Dr. ʿUmar al-Ḥakīm opinions about the term dārah and it therefore, appears wrongly in the Dictionary of Geographical Terms (Muʿjam al-Muṣṭalahāt al-Jughrāfīyah, p. 219)

Research into Arabic maps

Many academics belittle Arabic mapmaking, considering it to be an art at which the Arabs did not have a great deal of success. This is despite the good efforts invested by a number of researchers such as Conrad Miller and Yūsuf Kamāl which have resulted in raising the reputation of Arabic mapmaking to a sound level in many quarters. Unfortunately, only a small number of the sources left behind in the production of Arabic maps, have managed to reach us, and the same is applied to drawn copies of those sources.

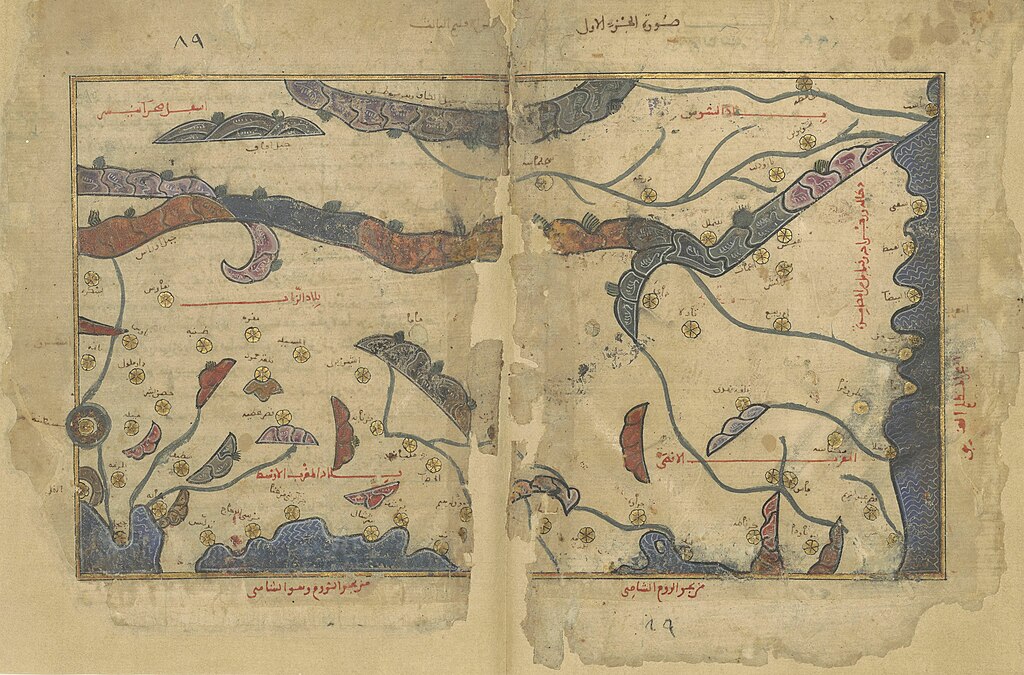

Arab mapmaking emerged concordantly with developments in Arab regional geography. Two clearly distinct schools existed in this field. The first was an approach that used astronomical zones and was influenced by the Greek tradition. The second was a descriptive regional geography that was exclusive to the Arabs. Each of these two distinct lines of approach gave rise to a particular kind of map, with their own special distinctions and characteristics.

The regional astronomical approach (the Greek school)

The ideas of the Romans and Greeks found their way into Arabic literature through a number of translations beginning with Ptolemy’s Geographia and Almagest. The Greeks and the Romans divided the inhabited regions of the world into seven zones according to a scheme of belts which extended from east to west starting from a latitude of 16° south, which marks the beginning of the first zone, and continuing up to around latitude 63° north which marks the end of the seventh zone.

Muḥammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī is recognised first exponent of this school. The title of this book, Ṣūrat al-ʾArḍ, is a literal translation of the word ‘geography’. It is not, however, a simple translation of Ptolemy’s book since, although it includes Ptolemy’s material, there are also extensive additions from the field of Arab geography.

Al-Khwārizmī’s book formed a part of the vast enterprise completed in the age of al-Maʾmūn, who enlisted numerous scientists and wise men to examine the books and studies of the Greeks and to test their assertions about the divisions of the earth. The resultant knowledge was collected and combined with that in the astronomical tables from the almanac (zīj) of al-Maʾmūn to produce the Maʾmūn representation or drawing, otherwise known as the ‘al-Maʾmūn map’, the first Arab map to represent the world, including the planets and the stars, lands and seas, its populated and desolate regions and its centres of habitation, cities and much more besides. Al-Masʿūdī compared this map with its predecessors and said, ‘It is better than the geography of Ptolemy and Marinus and others managed to create.’

The al-Maʾmūn map disappeared since several centuries. The last mention of it was a copy of the book with the oddly spelt title, al-Jaghrāfīyā by Abū ʿAbdallāh al-Zuhrī who died in the middle of the sixth century hijrī. According to what appears in al-Zuhrī’s book, the map he is referring to was circular, coloured and enclosed by two rings. One ring was blue and represented the sea, described as the sea of darkness. Inside it touched another ring, this time green, which marked the line of the sea which encircled the earth with its immediate territories on all its sides and from which all the seas branched out.

While the illustration mentioned, is itself no longer available, the scientific principles on which it was based were developed in the frame of a collection of astronomical tables used to determine different geographical locations. Among these were al-Zīj al-Ṣābī by al-Battānī, who spent his life closely observing the celestial bodies, and works by Ibn Yūnis in Egypt, al-Zirqālī in Andalusia and others. These tables, which were not accompanied by maps to indicate the places mentioned in them, could, however, be transferred to maps, with the provision that they were based on reliable copies.

The most important Arab effort of the astronomical-zone approach which followed the Greek school was the book, Nuzhat al-Mushtāq fī Ikhtirāq al-Āfāq by al-Idrīsī which was completed on the orders of King Roger II of Sicily. In this work the earth is divided into seven horizontal zones, each zone then being sub-divided into ten parts. Each of these parts has a map of its own followed by three maps: one showing a picture of the world, another showing what lies in the first zone and the last one showing what lies in the seventh zone. There are 73 maps in total. Al-Idrīsī repeated this work later in a smaller book, Uns al-Muhaj wa Rawḍ al-Furaj which was written for King Guillaume II.

It is obvious from these maps that al-Idrīsī has been committed - to some extent- to impose a rigidly coherent scale of measurements on all the different maps which made up the various zones. If it had not been for that, Conrad Miller would, for example, have been unable to put all the sections together to publish one complete map consisting of all the parts. In a similar token, al-Idrīsī used the same colour scheme throughout for all the features which appear on the various maps. Thus, mountains are brown in colour, seas are blue while rivers are green and so on. Furthermore, he followed the curving coastline to provide an overall picture which included all the zones he had described.

The regional descriptive approach (the Arabic school)

This approach can be identified in the work of a number of Arab geographers dating from the third century hijrī. The leading figures in the school were al-Iṣṭakhrī, ibn Ḥawqal and al-Maqdisī. The division of the inhabited world by this group differed from that of the Greek school. The zones they adopted were places that were characterised by physical and human characteristics. The books of this school contained 21 maps covering the zones described, which conform to the system used in the astronomical school. First there is a circular map of the world followed by more detailed maps of areas such as the Arabian Peninsula, the Persian Gulf, Morocco, Egypt, Syria and the Mediterranean. These are followed by 14 maps showing parts of the Islamic world, both central and east: the Arabian Peninsula, Iraq, Khozistan, Iran, Crimea, Sind, Armenia and Azerbaijan, as well as Jibāl, Jilān, Tabaristan, the Khazr Sea, the Persian desert, Sajastan, Khorasan, and the lands beyond the river (Mesopotamia).

In the order of the distribution of the maps and the manner in which they were made there is little sign of any close link with the work of the Greek school on zone studies. The term zone in this case refers to the particular geographical area depicted on the map. Each map is independent of all the others; they cannot be linked together to form one complete map of the world. These are illustrative maps which make use of straight lines and geometry, in order to trace the coastlines of rivers and seas. What we have here, is an entirely different approach from the one previously outlined. The examples described here do not constitute a neglect of the art of mapmaking, but are rather an explanatory method whose implications reach down to the present day and succeed in teaching about the systemisation of natural features, without referring to other less essential details.

To continue I should like to mention other maps which appeared in a number of books of Arab geography but which do not belong to either of the two schools mentioned above. These are maps like those which appear in Ibn al- Wardī’s book, Kharīdat al-ʿAjāʾib wa Farīdat al-Gharāʾib, as well as those of Tanīs and Qazwīn in the book Āthār al-Bilād wa Akhbār al-ʿIbād by al-Qazwīnī and the map of the Nile which appears in the book Nayl al-Rāʾid fī al-Nayl al-Zāʾid by Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad al-Ḥijāzī and Mabdaʾ al-Nīl by Jalāl al-Dīn al-Sīyūṭī and many others.

If we try to assemble all these various efforts we would only succeed in accumulating a list of those maps which are no longer available to us. There is no trace to be found of the original sources of the maps of al-Khawārizmī, who played a part in the creation of the Maʾmūn map. Nor is any trace to be found of the original source of al- Iṣṭakhrī’s book, nor that of Ibn Ḥawqal, nor al-Maqdisī. The maps of al-Idrīsī which are available to us nowadays date back no further than the ninth century hijrī, that is, they were drawn more than two centuries after al-Idrīsī himself wrote his book.

The attitude of the scribes to illustrated material also varied between complete omission, neglecting to draw the map on the back of the geographical text, leaving an empty space, or making a rough, inaccurate sketch of the map. This meant that with each new transcription of the book we moved further and further away from the original source. This also explains why it is possible to find clear discrepancies between the same maps that appear in different copies of the same book. This, for example, is the case with the book Nuzhat al-Mushtāq fī Ikhtirāq al-Āfāq or Uns al-Muhaj wa Rawḍ al-Furaj by Idrīsī. Scribes were also, to some extent, responsible for the discrepancies which appear in the maps of al-Iṣṭakhrī. In the copies of the book which are available to us nowadays the Mediterranean Sea sometimes appears to have a spherical form and in others it is oval, while in yet others it is circular and so on.

The attitude of the scribes is not, however, comparable with that of present-day researchers, the majority of whom ignore the value of maps, considering them to be mere accessories to the written text. They do not entitle themselves to the matter of interpreting the maps or studying the relationship between them and the text to which they are bound, to verifying the names of places, rivers, mountains and seas which they contain, nor to the work needed to place a given map in relationship to others, which appear in different copies of the book. Such examinations can help to distinguish differences in the copy under scrutiny and establish it as a part of the verification process. In a similar way, the Dictionary of Geography reproduces maps in just two colours - black and white. we find this in the studies of al-Masālik wa al-Mamālik by al-Iṣṭakhrī (Cairo, 1961), Ṣūrat al-Arḍ by Ibn Ḥawqal (published in Europe and Beirut) and Uns al-Muhaj wa Rawḍ al-Furaj in its Latin editions. All of these were published as illustrated editions by the Institute of the History of Arabic and Islamic Sciences in Frankfurt (1984). It hardly needs to be mentioned that colour is of great importance to the maps mentioned here and to neglect it, is to omit an important portion of the material which these maps contain. Finally, the researchers do not publish the maps in the same scale that they have in manuscript form. Thus, they reject an obvious feature of the book under examination. They enlarge what is small and they reduce what is large to comply with the demands of publication and modern page sizes. To publish maps in a different scale is something which demands great caution since there is actually some point and purpose to the original scale.

Much could be done to reduce such lapses in the reproduction of maps from the manuscripts of the Arabic geography heritage if geographers were more involved in the work of publishing this heritage and shared in the analysis of this material, which is, after all, part of a specialised field.

Conclusion and recommendations

I shall conclude this chapter on the general condition of research into the Arabic geography heritage by making three points.

First, early texts should be republished after an examination to determine their rarity and the availability of new manuscripts that could be used to correct problems which exist in previous editions. Secondly, more recent books have not paid enough attention to the correction of the terms used in subject headings and to the confirmation of localities. There has been no attempt to research the specific manuscripts of a book in order to contextualise the investigation, and as a result no benefit can be derived from the investigation. Thirdly, there are books and geography thesis that do not fulfil the obligations of their research. The libraries of both east and west are full of such works, which make one wonder how they ever managed to get published. This final point, which has not been dealt with, in this research, is that one is only too familiar to those who work with geographical manuscripts and yet, despite this familiarity, the failure from which the study of geographical manuscripts continues.

I would like to make a number of recommendations on the basis of what has been written above.

- There should be an analysis of the books of the Arabic geographical heritage which were published in the past. No dependable new editions have emerged. The manuscripts upon which most of the known editions and publications were based should be identified, with respect to assessing their content and significance as sources for new editions. There should be a study of the general state of the books published in the last decades to determine the value of their contribution to any further study.

- A scientific council should be set up composed by a number of specialists who have knowledge of the texts and its aim being to ensure the verification of material, including a thorough revision of the available copies of the manuscripts, as well as the copies made from the original sources which appear in other texts. This revision should also benefit from critical studies which were written after books were first published. Among the duties of the council should also be the question of linguistic accuracy and revision and the highlighting of differences between manuscripts and academic writing.

- Collections of studies of the manuscripts of the Arab geography heritage should be prepared, comparing early and later work as well as outlining the scientific supplements which these heritage works contain. Critical studies should be encouraged that include published research. These tasks should be carried on until some system of regulation and scientific accuracy is imposed on the study of the heritage works.

- A dictionary of geographical terms used in the heritage texts should be prepared, which should pay particular attention on what appears in Muʿjam al-Buldān. Such a dictionary would benefit from the names of subject headings and places in Arabic which are, for the most part, descriptions of the earth and its features. It is certain that this work would help in compiling present-day linguistic dictionaries.

- There should be an assessment of research work that was carried out in the past on the Arabic geographical heritage and, in particular, on what was written by orientalists. There should also be an evaluation of the work done to translate valuable material from this tradition into Arabic.

- It is necessary to evaluate recently published research work and thesis connected with the geographical heritage. Any wrong place-names and geographical terms should be identified and the correct terms disseminated in relevant journals and periodicals.

- The importance of Arabic maps should be appreciated. The work of Yūsuf Kamāl and Conrad Miller on Arabic maps should be revised in addition to maps which were not studied or worked on by these two men. Any such publications must maintain the same colours and scale as those used in the manuscript.

Sources and References

Al-Azharī, Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad, Tahdhīb al-Lughah (Cairo, 1994).

Al-Bakrī, Abū ʿUbayd ʿAbdallāh ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz, Jazīrat al-ʿArab min Kitāb al-Masālik wa al-Mamālik, ed Abdallah al-Ghunaim (Kuwait, 1977).

- Al-Masālik wa al-Mamālik, ed Adrian Leeuwen and Andrē Ferre (Tunis, 1992).

- Muʿjam ma Istaʿjam min Asmāʾ al-Bilād wa al-Mawāḍiʿ, ed Mustafa al-Saqqa, Cairo (1945-1951) and the al-Azhar manuscript collection no. 262.

Bartold, V.V., Tārīh Turkistān min al-Fatḥ al-Islāmī ilā al-Ghazw al-Maghūlī (Kuwait, 1981).

Ibn Faḍlān, Aḥmad ibn Faḍlān ibn ʿAbbās, Risālat Ibn Faḍlān, ed. Sami al-Dahhan (Damascus, 1959).

Abū al-Fidāʾ, ʿImād al-Dīn Ismāʿīl, Taqwīm al-Buldān, ed Reinaud and de Slane (Paris, 1848).

Al-Ghunaim (Abdallah Yusuf), Maṣādir al-Bakrī wa Manhajuhu al-Jughrāfī, 3rd edition (Kuwait, 1998).

- Al-Makhṭūṭāt al-Jughrāfīyah al-ʿArabīyah fī al-Maktabah al-Brītānīyyah wa Maktabat Jāmiʿat Cambridge (Kuwait, 1999).

- Istinbāṭ al-Muṣṭalahāt al-ʿArabīyah lil-Ashkl al-Arḍyahʾ, al-Majallah al-ʿArabīyah lil-ʿUlūm al-Insānīyah, Kuwait University, vol. 3, No 12 (1983), pp. 13-36.

Al-Ḥakīm, ʿUmar, Tamhīd fī ʿIlm al-Jughrāfīyā ʿal-Taḍārīsʾ (Damascus, 1965).

Al-Hamdānī, al-Ḥasan ibn Aḥmad, Ṣifat Jazīrat al-Arab, ed Muhammad ibn Ali al-Akwaʿ (Beirut, 1974).

al-Ḥamawī, Yāqūt, Muʿjam al-Buldān, ed Wüstenfeld (Leipzig, 1866).

Al-Idrīsī, Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad, Nuehat al-Mushtāq fī Ikhtrāq al-Āfāq (Rome, 1977; Beirut, ʿĀlam al-Kutub, 1989.

al-Iṣṭakhrī, Ibrāhīm ibn Muḥammad, Al-Masālik wa al-Mamālik, ed. by Muhammad Jabir al-Hayni (Cairo, 1961).

Al-Kindī, ʿUmar ibn Muhammad ibn Yūsuf, Faḍāʾil Maṣr, ed. Ibrahim Ahmad al-ʿAdawi and Ali Muhammad Umar (Cairo, 1971).

Kranchokvsky, Ignatius, Tārīkh al-ʿAdab al-Jughrāfī al-ʿArabī, trans. Salah al-Din Uthman Hashim (Beirut, Dār al-Gharb al-Islāmi, 1987).

Ibn Khurdādhdhbih, ʿAbdallāh ibn ʿAbdallāh, Al-Masālik wa al-Mamālik, ed de Goeje (Leiden, Maktabah al-Jughrāfīyah al-ʿArabīyah, 1889).

Le Strange, G., Buldān al-Khalāfah al-Sharqīyah, trans. Bashir Francis and Kurkis Awwad (Baghdad, 1954).

Al-Maqdisī, Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad, Aḥsān al-Taqāsīm fī Maʿrifat al-Aqālīm, ed de Goeje (Leiden, al-Maktabah al-Jughrāfīyah al-ʿArabyah, 1906).

Ibn Rustah, Aḥmad ibn ʿUmar, Al-Aʿlāq al-Nafsīyah, ed de Goeje (Leiden, al-Maktabah al-Jughrāfīyah al-ʿArabīyah, 1892).

Al-Sayyad, Muhammad Mahmud, Al-Muʿjam al-Jughrāfī, (Cairo, Academy of the Arabic Language, 1974).

Sousi, Muhammad, ‘Mushkilat waḍʿ al-Muṣṭalaḥ’. Majallat al-Lisān al-ʿArabī, Rabat, vol 12, no. 1, pp.9-15

Tuni, Yusuf, Muʿjam al-Muṣṭalaḥāt al-Jughrāfīyāh (Cairo, 1964).

Al-Zahri, Muḥammad ibn Abū Bakr, Kitāb al-Jughrāfīyah, ed Muhammad al-Haj Sadiq (Beirut, 1965).

| Source note: This was published in: The Earth and its Sciences in Islamic Manuscripts: proceedings of the fifth conference of Al-Furqān Islamic Heritage Foundation – English version, 2011, Al-Furqan Islamic Heritage Foundation, London, UK., p 31-68. Please note that some of the images used in this online version of this article might not be part of the published version of this article within the respective book. |